The Prime Minister’s Office is expected to provide all manner of assistance to the Prime Minister. Hence it has to be headed by those who reject piecemeal solutions and are more focused on structural improvements that can unite and cohere the country

By Arun Bhatnagar

- Nehru had kept a compact personal secretariat headed by a Principal Private Secretary to help him with routine papers

- The establishment attached to the Prime Minister was rechristened the PMO when Morarji Ranchhodji Desai took office in March 1977

- The Principal Secretary at the time – Prof Prithvi Nath (PN) Dhar was among Indira Gandhi’s closest advisers

- LN Jha created a centre of authority that rose to centrality during regime of PV Narasimha Rao

THE existence of a civil service structure at the apex of the Government of India predates Independence, if one were to take into the reckoning the position of Private Secretary to the Viceroy and Governor General, once held by Sir Evan Meredith Jenkins, ICS (1896 – 1985), last British Governor of the Punjab, and by Sir George Abell, ICS (1904-89), who succeeded Jenkins in the tenures of Wavell and Mountbatten.

Jenkins entered the ICS in 1920, held various posts in the Punjab and was appointed Chief Commissioner of Delhi. Owing to disturbances engulfing the Punjab, Malik Khizar Hayat Tiwana resigned as Premier of the province in March, 1947 and Jenkins, as Governor, assumed direct control until the day of Partition viz.14 August, 1947.

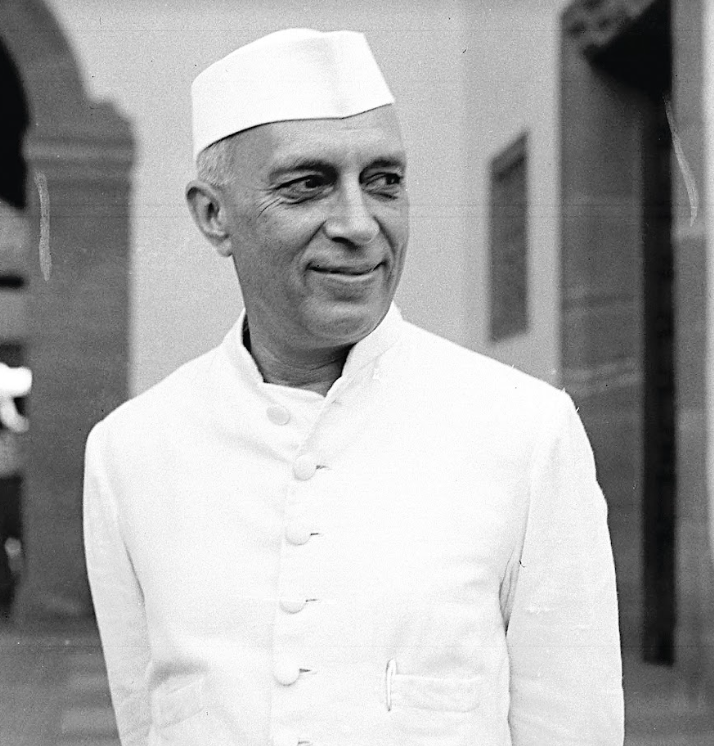

Jawaharlal Nehru was, in strictly legal terms, Vice President of the Viceroy’s Executive Council in 1946-47 and was looked upon as head (and virtually the Premier) in the Interim Government. But he was not a Prime Minister.

Nor is the PMO of today the same entity as the Prime Minister of the day, although this is loosely construed to be the case.

The PMO, presided over by a Principal Secretary, is expected to provide all manner of assistance to the Prime Minister, in current times. It includes the anti-corruption unit and the public wing dealing with grievances and houses hand-picked bureaucrats – including the National Security Adviser (NSA) of high rank – to oversee and coordinate the working of the government.

TRANSITION TIME

As Prime Minister, Nehru had kept a compact personal secretariat (PMS) headed by a Principal Private Secretary (of the level of Joint Secretary in the Government of India) to help him with routine papers. An early incumbent was Dharma Vira (ICS, UP, 1929) and Kesho Ram (ICS, Bengal and, later, UP, 1938) was the last.

In 1946, Mundapallil Oommen (MO) Mathai, (1909-1981) became Nehru’s Private Secretary. He was born to a traditional Marthoma Syrian Christian family in central Travancore. CD Deshmukh, once a Finance Minister in the Nehru cabinet, described him as the ‘most powerful acolyte of the PM’.

Mathai’s functioning was not confined to the formal organization that existed for the Prime Minister to whom he had direct access. Over the years, he became controversial and was eased out when an enquiry conducted by the then Cabinet Secretary, Vishnu Sahay (ICS, UP, 1925) did not clear him of charges of misuse of power.

He went on to write books of even more controversial content.

One of his less contentious articles on the Nehru years was titled ‘The Scientific Trio’ in which he spoke of SS Bhatnagar, PC Mahalanobis and HJ Bhabha – all Fellows of the Royal Society – who enjoyed the Prime Minister’s confidence in a special measure.

Mathai was the first in a line of individuals of humble beginnings – Yashpal Kapoor, RK Dhawan, among others – who came into the enjoyment of disproportionate prominence. These men were often in the know of extremely sensitive matters; Dhawan and ML Fotedar became Union Ministers in Congress governments.

GROWING INTO POWER CENTRE

At this point itself, it may be mentioned that, post-Emergency, a former Rajasthan Chief Minister, Harideo Joshi (1921-95), a senior Congressman, and the State Chief Secretary, Mohan Mukherjee, IAS made startling disclosures before the Justice JC Shah Commission in November, 1977, stating that even a telephone call from RK Dhawan (1937-2018) was considered as having the sanction of the Prime Minister (Indira Gandhi) and the Union Government behind it. Justice Shah (1906-91) could not contain his amazement that the two of them had equated ‘the august Mr Dhawan’ with the PM. The Commission heard how Joshi and Mukherjee, after receiving telephonic instructions from Dhawan, had acted with great expedition to order the detention of a Jaipur advocate under MISA and the termination of his wife’s services from a government school. On Dhawan’s directive, they asked a senior IAS officer – Mangal Behari – to proceed on leave.

As Nehru’s Private Secretary, Mathai’s LEFT functioning was not confined to the formal organization that existed for the Prime Minister to whom he had direct access. Over the years, he became controversial and was eased out when an enquiry conducted by the then Cabinet Secretary, Vishnu Sahay

Such was the precarious condition of the PMO in the decade following the demise of Nehru and Lal Bahadur Shastri. The Principal Secretary at the time – Prof Prithvi Nath (PN) Dhar (1919-2012) – was among Indira Gandhi’s closest advisers, collectively known as the ‘Kashmiri Mafia’; his wife, Sheila Dhar (1929-2001), a Mathur kayastha of Old Delhi, was an author and a singer of the Kirana Gharana.

In June, 1964, Prime Minister Shastri, took steps to form a full-fledged Secretariat. A highly regarded member of the ICS, the Lakshmi Kant (LK) Jha (Bihar, 1936), a Maithili brahmin born in Darbhanga district, who had served as an Additional Secretary with him when Shastri was the Minister of Commerce and Industry was identified for the crucial position of Secretary to the Prime Minister, alongside two IAS Joint Secretaries, both kayasthas, of the Uttar Pradesh cadre, namely, CP (later Sir) Srivastava and Rajeshwar Prasad, subsequently a much-remembered Director of the IAS Academy at Mussoorie.

Jha drafted Shastri’s key policy statements and the Prime Minister’s Secretariat, through his forceful personality, fast became a major power centre. It exerted influence on various issues, especially in the vital spheres of economic affairs and foreign relations.

He can be said to have created a centre of authority at the very top that curtailed the importance of the Cabinet Secretary which again rose to centrality during the regime of PV Narasimha Rao (1991–96) when Naresh Chandra (IAS, Rajasthan, 1956) headed the Cabinet Secretariat and the redoubtable AN Varma (IAS, Madhya Pradesh, 1956) was Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister.

PNH’S POWERFUL INFLUENCE

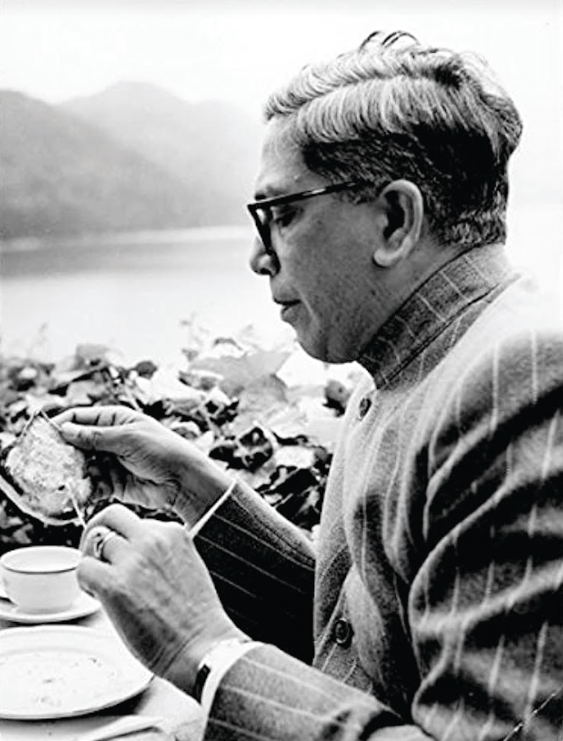

Under Indira Gandhi, LK Jha carried on as Secretary to the new Prime Minister, before handing over the baton in 1967 to Parmeshwar Narayan (PN) Haksar (1913-98) of the Foreign Service who had been the Indian Ambassador to Austria.

The 1967 election witnessed a few ‘shock’ defeats, such as of K Kamaraj, the Congress President, from the Virudhunagar State Assembly seat in Madras (Tamil Nadu) and of SK Patil to the Lok Sabha from the Bombay South constituency. Good fortune was beginning to smile on Indira Gandhi as the process commenced of the dismantling of the Syndicate which had catapulted her to power in the first place. His sincerity and trustworthiness never in doubt, the stage was now set for P N Haksar’s intellectual calibre and political acumen to be put to the test.

P N Haksar or PNH has been described as ‘an intellectual powerhouse and one of India’s most successful strategists who astutely established the political omnipotence of a relatively weak Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi’ through path-breaking measures like the Nationalization of the 14 largest Commercial Banks in 1969 which, in turn, saw the exit of Morarji Desai from the cabinet

P N (Babboo) Haksar or PNH has been described as ‘an intellectual powerhouse and one of India’s most successful strategists who astutely established the political omnipotence of a relatively weak Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi’ through path-breaking measures like the Nationalization of the 14 largest Commercial Banks in 1969 which, in turn, saw the exit of Morarji Desai from the cabinet. Haksar felt that ‘the best way to vanquish the Syndicate would be to convert the struggle for personal power into an ideological one’.

From 1967 to 1973, PNH was arguably the most powerful person in the government. He shared his influence with four others – Kashmiri Brahmins, like him – namely, DP Dhar, a politician turned diplomat who had served as a deputy minister under Sheikh Abdullah in the early 1950s in J&K, TN Kaul, a career diplomat who rose to be Foreign Secretary, PN Dhar, an economist turned bureaucrat and RN Kao (IP, 1940), a police officer turned super spy and security specialist. Their caste links were strong and they were part and parcel of Indira Gandhi’s innermost coterie.

He played a key role in negotiating the 1972 Simla Agreement with Pakistan and may have been the only one on the Indian side who was privy to the secret negotiations that took place between Indira Gandhi and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto over the Kashmir issue which remains a volatile flashpoint; armed militants have long been indulging in violence that has claimed thousands of lives, young and old.

One of the actions for which PNH has invited criticism relates to the advice he, apparently, proffered to Indira Gandhi to let Bhutto “off the hook” at Simla (now Shimla) and not to insist on the Cease Fire Line being recognized as the International Boundary. India did not take advantage of the defeat inflicted on Pakistan in December, 1971; the Simla Agreement has been perceived as a political failure because of the Indian government’s inability to obtain a final settlement on Kashmir. Years later, when the late General Musharraf was said to have proposed a peace formula, Atal Bihari Vajpayee lost the opportunity to have the LoC recognized as an international border.

It was a measure of Haksar’s overriding importance at Simla that he (and not TN Kaul, technically senior in the Foreign Service) led the delegation of Indian officials for the discussions with their Pakistan opposite numbers.

PNH’s leftist leanings served the Prime Minister well in projecting a ‘Garibi Hatao’ image that was further reinforced (before the 1971 general elections that were called a year ahead of schedule) through the abolition of the privy purses and privileges of the erstwhile Princes; with so many Indians so poor, these privileges were, in the words of PN Haksar, ‘out of place and out of time’. Land reform policies were also introduced.

On the minister-civil service relationship, PNH held the view that ‘ministers must have the skill, the will and sense of direction for riding the bureaucratic horse ….. this will require not merely ability but character and integrity’.

ATMOSPHERE OF ANIMOSITY

Indira Gandhi was known to peremptorily discard her closest colleagues, one such being Pt DP Mishra, a key political adviser between 1963–72. Haksar’s turn to leave coincided, broadly, with the rise of Sanjay Gandhi who was increasingly unhappy about the Principal Secretary’s influence over his mother. PNH was shifted to the Planning Commission where he also made a sterling contribution.

The Emergency was not long in coming; in the elections which were held in 1977, the Congress was wiped out and both Indira and Sanjay Gandhi lost their seats. There were many who thought that if PNH had still been at Indira Gandhi’s side, the situation would not have spiralled out of control.

When questions began to be asked in Parliament about Sanjay Gandhi’s ‘small car’, Haksar advised the Prime Minister to abandon the Maruti project and extricate herself from the controversy. His opinion was disregarded.

Indira Gandhi’s tendency to reward favourites in the civil service unsettled the bureaucracy by enhancing factional splits and disputes. During the Emergency, the IAS stood forth as the ruling elite, taking orders directly from the Prime Minister’s confidants. The IAS mechanism was positioned to manage the Emergency throughout the country.

Such was the atmosphere of animosity obtaining under the Emergency that PNH’s relatives in Connaught Place, New Delhi were raided on flimsy grounds.

From 1967 to 1973, PNH was arguably the most powerful person in the government. He shared his influence with four others – Kashmiri Brahmins, like him. Their caste links were strong and they were part and parcel of Indira Gandhi’s innermost coterie

PNH’s personal connection with Indira Nehru – as she then was – and Feroze Gandhi (1912-60) went back many years to the London of the late 1930s. One of Feroze Gandhi’s friends and a fellow Member of Parliament recalled in 1977 that he (Feroze) looked forward to leisurely chats with PNH.

Having failed the ICS examination in 1936, he took up legal practice in Allahabad, earned a name through his mentor, Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, and came to the notice of Jawaharlal Nehru.

To those who knew him, PNH was kind and generous. He counted Krishna Menon among his friends and intervened to arrange an alternate posting at the Centre for the outgoing Home Secretary, NK Mukarji (ICS, Punjab, 1943) who faced reversion to the parent cadre at the beginning of the Emergency.

In January 1973, Haksar declined the Padma Vibhushan and informed the then Union Home Secretary that he would be grateful “… if you will kindly convey to PM my deep and abiding gratitude for the privilege I had to serve under her.”

A month earlier, the Prime Minister had written to him to say: ‘During a period which has spanned so many crises, you have stood like a rock. Your wise guidance has been invaluable in helping us to negotiate the obstacles and steer clear of the many pitfalls ….. There can be no doubt that your retirement will greatly diminish the efficacy of the P.M.’s Sectt. and will be a great loss to me…..’

She addressed him as Haksar Saheb, whereas LK Jha was just LK.

PNH left the Planning Commission in 1977 (he had been the Deputy Chairman for a little over two years), by when relations with the Gandhis had really cooled.

When his mother died in April, 1979, Indira Gandhi was out of power. Being a very correct person, she asked her Social Secretary to accompany her on a condolence visit to PNH. No prior intimation of the visit had been given and no words were exchanged between her and PNH, with the Social Secretary doing the talking and trying to minimize the embarrassment.

DEVOID OF EXCELLENCE

The establishment attached to the Prime Minister – hitherto known as the PMS – was rechristened the PMO when Morarji Ranchhodji Desai (1896-1995) took office in March 1977; his choice for the Principal Secretaryship fell on V Shankar (ICS, Bombay, 1932) who had been Deputy Prime Minister, Sardar Patel’s Private Secretary, uptil the Sardar’s passing in December, 1950. He had retired ten years earlier as the Defence Secretary and was preferred over Dr IG Patel, a brilliant economist and a Gujarati. Also in the race (as one of Desai’s favourites) might have been TP Singh Sr (ICS, Bihar, 1936), a former Union Finance and Agriculture Secretary, who, however, died early.

Lakshmi Kant Jha drafted Shastri’s key policy statements and the Prime Minister’s Secretariat, through his forceful personality, fast became a major power centre. It exerted influence on various issues, especially in the vital spheres of economic affairs and foreign relations

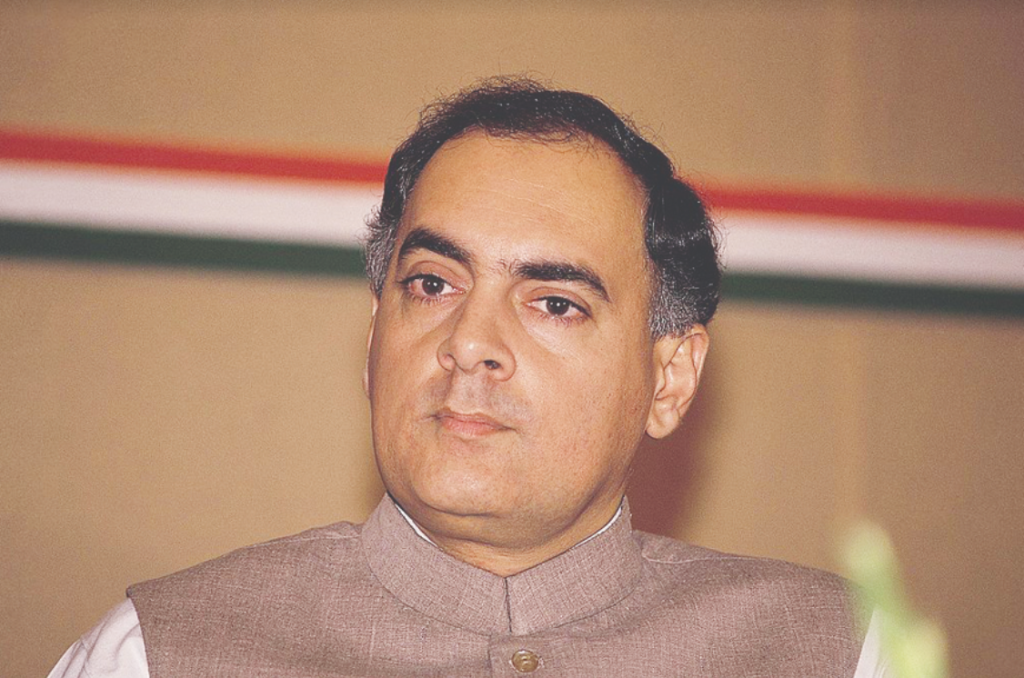

The Rajiv Gandhi government was rocked in its early months in 1985 by a serious spy scandal with alleged links to the PMO. A conman of an Indian firm who had established close connections with foreign missions was found to have been passing on photocopies of classified documents to his clients. The then Principal Secretary, PC Alexander, a retired IAS man (not of the ilk of LK Jha or PN Haksar but who was later to display lofty political ambitions) resigned owning moral responsibility for the lapse.

In trying to seek out the names of ‘knights in shining armour’ in the successive PMOs (not necessarily Principal Secretaries), an objectively-inclined investigator is likely to be hard put to come up with many candidates. Nonetheless, there are a few who might survive in administrative memory a bit longer, of whom CR Krishnasway Rao Saheb (IAS, AP, 1949) who rose to be Cabinet Secretary, BG Deshmukh (IAS, Maharashtra, 1951) who was Cabinet Secretary before being appointed Principal Secretary by Rajiv Gandhi, a post he continued to hold under VP Singh and, briefly, under Chandrasekhar, GK Arora (IAS, UP, 1957), Otima Bordia (IAS, Rajasthan, 1957), KR Venugopal (IAS, AP, 1962) and Nishi Kant Sinha (IAS, Bihar, 1966) are notable examples.

The mercifully short-lived regimes of late 1979, and of between 1996-98 were largely devoid of meritocracy; the post-2000 period has been no less pedestrian, except that nepotism and corruption have continued to thrive and the grant of Padma Awards has kept flowing.

Regrettably, a perception has been growing that the PMO is more a source of favouritism and meddlesome interference than of positive inspiration and productive guidance.

A classic instance of ineptitude was the handling of the crisis (last week of December, 1999) in respect of the hijacking of IC814 – which was on a flight from Kathmandu to New Delhi – when three dreaded terrorists had to be released in lieu of freeing the hostages. The present NSA was one of the negotiators in this ignominious exchange.

In his Autobiography, ‘My Country My Life’ (2008), Shri LK Advani, former Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister wrote about the Kargil Review Committee that was instituted in July, 1999:

“One of the Committee’s few recommendations not accepted was regarding the National Security Council (which had been set up by the Vajpayee government in April, 1999) and which read as follows: ‘Whatever its merits, having a National Security Adviser who happens to be Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister can only be an interim arrangement. The Committee believes that there must be a full-time National Security Adviser and it would suggest that a second line of personnel be inducted into the system as early as possible and groomed for higher responsibility.’

The Rajiv Gandhi government was rocked in its early months in 1985 by a serious spy scandal with alleged links to the PMO. A conman of an Indian firm who had established close connections with foreign missions was found to have been passing on photocopies of classified documents to his client

Many senior ministers in the government and I felt that there was much merit in this suggestion. We repeatedly urged the Prime Minister to bifurcate the two posts held by Brajesh Mishra. However, Atalji did not implement this recommendation ….. In my view, the clubbing together of two critical responsibilities, each requiring focused attention, did not contribute to harmony at the highest levels of governance”.

In functioning democracies, institutions like the Prime Minister’s Office stand in need of (and should be led by) those who refuse to consider piecemeal approaches and are more concerned with systemic changes which can make the country cohesive and coherent. Loyalty cannot be their only virtue and it must be accompanied by probity, ability and a capacity for tireless

work.