From the 1905 partition of Bengal to the modern political landscapes of India and Bangladesh, Bengal remains a crucible of cultural, political, and social change. In this exploration, Arun Bhatnagar delves into Bengal’s intricate history, its political evolution, and the enduring complexities of identity shaping the region.

By Arun Bhatnagar

- The Jamaat-e-Islami, rabidly anti-India and stridently pro-Pakistan, seems back in business in Bangladesh. it held a public rally in June, 2023

- India-Bangladesh ties have witnessed periods of ‘frostiness’ in the past, particularly under Begum Khaleda Zia’s Bangladesh Nationalist Party

- West Bengal’s Muslims, 27% of its population, are uneasy with Mamata Banerjee’s Hindu image. They shifted from the Left Front to the TMC in 2011

- Nehru and Sardar Patel were skeptical of Suhrawardy’s intentions and had veered to the view that he could eventually turn the tables

WHILE India and Bangladesh have both enjoyed amicable relations with the United States (Indo-US ties are, in fact, growing exponentially), Washington DC’s perceived opposition to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has the potential of putting New Delhi in a tricky situation. Apparently, the United States disapproves of political violence, human rights violations and election manipulation in Bangladesh. Several observers believe that this stance is meant to pressure Sheikh Hasina into reducing Beijing’s influence in Dhaka (Dacca).

India-Bangladesh ties have witnessed periods of ‘frostiness’ in the past, particularly under Begum Khaleda Zia’s Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) governments (1991-96 and 2001-06).

In New Delhi’s view, the BNP-backed by elements of the Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh – is extremist; India has built strong, stable relations with Sheikh Hasina and the Awami League, which augurs well for the Region as a whole. However, while the Indian Prime Minister may feel close to Sheikh Hasina, public sentiment in Bangladesh towards India is more complex.

The Jamaat-e-Islami, rabidly anti-India and stridently pro-Pakistan, seems back in business in Bangladesh; it held a public rally in June, 2023 – after ten years – in Dhaka. A massive turnout, especially of the Islami Chhatra Shibir (student wing) members, marked its return from the political wilderness.

General elections are scheduled to be held in Bangladesh around January, 2024. India’s preference should obviously be that the Awami League returns to power but New Delhi would, willy-nilly, have to deal with the BNP and its allies should they come out in a winning position.

Sheikh Hasina was among the world leaders invited to the G20 Summit in New Delhi and Bangladesh is a key player in India’s Act East and Neighbourhood First policies. She has warm personal relations with the Nehru-Gandhi family.

POLITICAL LANDSCAPE: PAST AND PRESENT

At its peak, the Bengal Presidency – also known as the Presidency of Fort William – was the largest administrative unit under the British in India, with the capital at Calcutta (Kolkata) and whose territorial jurisdiction covered parts of what is now South Asia and Southeast Asia, including Burma (Myanmar).

Historical Fort William was named after King William III of England, Scotland and Ireland (he reigned between 1689-1702) and sits on the eastern banks of the Hooghly. Today, it is the headquarters of the Eastern Command of the Indian Army.

The United States disapproves of political violence, human rights violations and election manipulation in Bangladesh, which some observers believe is meant to pressure Sheikh Hasina into reducing Beijing’s influence in Dhaka

Further to the east is the India-Bangladesh international border that reminds many of the birth of a sovereign nation in the early 1970s. The Bangladesh divisions of Mymensingh, Khulna, Rajshahi, Rangpur, Sylhet and Chittagong are situated along this land border (2545 miles), the fifth-longest in the world.

In West Bengal, the third term of the All India Trinamool Congress (TMC) and its supremo, Mamata Banerjee, which began in May, 2021, is proving to be a tough one.

The Muslims account for about 27 percent of the population and appear uneasy over Banerjee projecting Hindu credentials. Their shift from the Left Front to the TMC started around 2011 and, since then, the Muslim minority has been an important voter-base for Mamata Banerjee who has lately announced that the West Bengal Legislative Assembly have passed a Resolution and agreed on Poila Boishakh, the first day of the Bengali calendar, being observed as ‘Bangla Dibas’ (Bengal Day). The Rabindra sangeet, ‘Banglar Mati, Banglar Jal’ is the new State Anthem.

She has termed the TMC’s win on September 8, 2023 in the Dhupguri bye-election as a ‘big victory not just for North Bengal but also for the whole of Bengal’. The outcome in the constituency, which is located in the Jalpaiguri district – dotted with tea gardens – has come as a setback to the Saffron Party.

The electoral performance of the TMC in the next Lok Sabha polls would doubtless have a bearing on the prospects of an Opposition Alliance at the national level.

FIRST PARTITION OF BENGAL

The First Partition of Bengal in 1905, during the viceroyalty of Lord Curzon, resulted in the short-lived provinces of Eastern Bengal and Assam. In 1912, Bengal was reunited, while Assam (and Bihar and Orissa) emerged as separate provinces. The latter was further split up in April, 1936 into the provinces of Bihar and Orissa (Odisha).

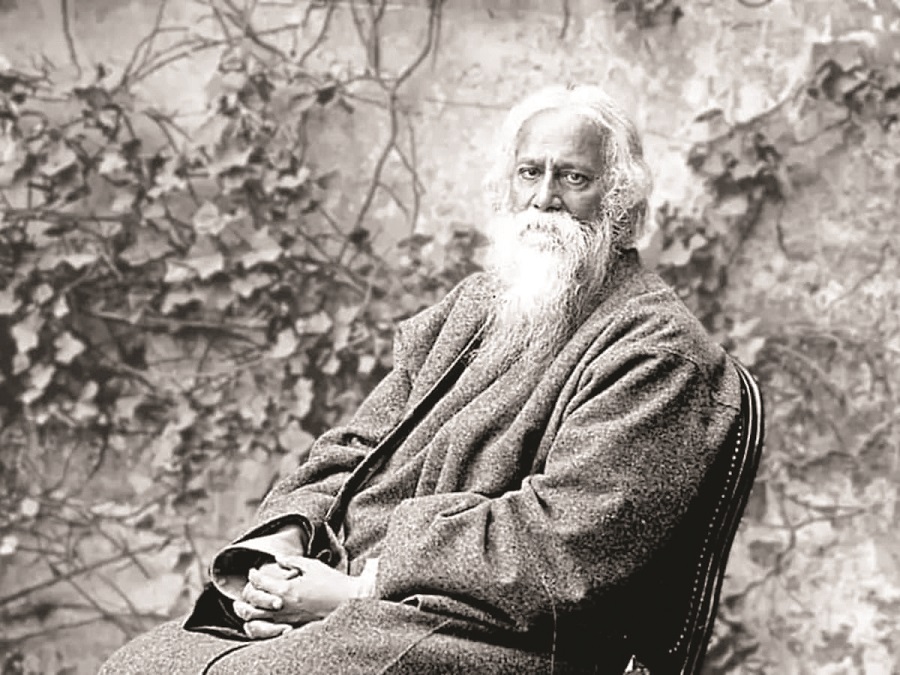

The English-educated middle class of Bengal, the bhadralok, saw the Partition as a measure to diminish their influence. The actual day of partition (16 October, 1905) happened to coincide with Raksha Bandhan and Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore (a future Nobel Laureate) urged that rakhis be tied, especially to Muslims, to emphasize inter-religious bonds and that Bengal was against division.

The Partition triggered radical nationalism and was seen as a ‘divide and rule’ policy. When it was annulled, the districts where Bengali was spoken were again unified. Nonetheless, sections of Muslims were disappointed and felt that their interests had been compromised for Hindu appeasement.

CONTROVERSIAL CONSEQUENCES

Sir Khwaja Salimullah (1871-1915), the then Nawab of Dacca residing at the historic Ahsan Manzil, actively garnered support for the Partition of Bengal and convened a meeting of the Mohammedan Educational Conference at his own cost. Over two thousand invitees gathered at the Nawab family’s garden-house in Shahbag, Dacca in December, 1906 when the All India Muslim League was founded with Khwaja Salimullah as Vice President.

In later years, his nephew, Sir Khwaja Nazimuddin was, successively, Governor General and Prime Minister of Pakistan.

Still later, in 1975, at the request of Pakistan Prime Minister Z A Bhutto, then visiting Bangladesh, Khwaja Salimullah’s grandson, Major Khwaja Hassan Askari – who had served with the 5th Regiment of the Armoured Corps (Probyn’s Horse) and was the last titular Nawab – migrated from Dhaka to Karachi.

In Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s opinion, he should have continued to live in Bangladesh with his people. He died in August, 1984 and was laid to rest at the Defence Graveyard in Karachi where his wife, Begum Bilquis Askari, was buried in 1995.

Thus, in the end, the pull of Pakistan was stronger than the ancestral roots in East Bengal.

A senior Bengali politician, Nurul Amin (1893-1974) stayed loyal to Pakistan and was the Prime Minister for no more than thirteen days in December, 1971. He was also the only Vice President, to date, of Pakistan (December, 1971 – August, 1973) and is regarded as a traitor in Bangladesh.

Many anglicised Bengalis belonged to the Brahmo Samaj and most had origins in East Bengal; those in the ICS were usually more ‘pucca’ than others in the Service.

THE TRAGEDY OF AUGUST 1946

In 1946, apprehensive of Hindu domination in the Constituent Assembly, Jinnah rejected the Cabinet Mission Plan immediately after Jawaharlal Nehru’s contentious Press Conference in Bombay (Mumbai) which was followed by his own in the same city.

Jinnah’s stand was hardening and he declared that if the Muslims were not conceded a separate Pakistan, then they would launch ‘direct action’. When asked by pressmen to be more specific, he retorted: “Go to the Congress and ask them their plans. When they take you into their confidence, I will take you into mine. Why do you expect me alone to sit with folded hands?”

He announced 16 August, 1946 as ‘Direct Action Day’ and warned the Congress: “We do not want war. If you want war, we accept your offer unhesitatingly. We will either have India divided or India destroyed …… This day we bid goodbye to constitutional methods …. I am not prepared to discuss ethics. We have a pistol and are in a position to use it”.

The National Unionist Party in Punjab, representing various communities including Muslims, Hindus (Jats) and Sikhs, was led by prominent figures like Sir Fazli Husain, Sir Chhotu Ram, and Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan. They vehemently opposed the Partition of India. Khizar made a final effort to persuade the British government to consider his proposal for an independent Punjab separate from both Pakistan and India

The Chief Secretary, R L Walker, and the Muslim League Premier, Huseyn Shaheed (HS) Suhrawardy, advised the Governor, Sir Frederick John Burrows (1887-1973) to declare a public holiday on that day which was agreed to.

Walker, a seasoned administrator, had entered the ICS in 1920 in the Chittagong Division, home to Cox’s Bazar, the world’s longest unbroken, natural sea beach and St. Martin’s Island, a coral reef. His proposal was well-intentioned and made in the expectation that the risk of conflict would be reduced if government offices, commercial establishments and shops remained closed throughout Calcutta on 16 August.

It had an opposite effect. The troubles spread quickly, instigated by journalists and others. The League’s rally at the Ochterlony Monument was described as the ‘largest ever Muslim assembly in Bengal’; the main speakers included Khwaja Nazimuddin and Suhrawardy who were idolized by Urdu-speaking Muslims.

In Bengal, the Muslim community was concentrated in the countryside; Calcutta had a clear Hindu majority (73% of the population, according to the 1941 census) and a Muslim minority (23%). Most Muslims lived in North Calcutta, while Central and South Calcutta were almost exclusively Hindu, with a sprinkling of Europeans.

The violence that lasted four days (16-19 August) was unbelievably tragic and remains exceedingly ‘controversial’, notwithstanding a degree of consensus on the magnitude of the killings (5000-10,000 dead and over 15,000 injured or wounded). The unanswered questions pertain to the exact sequence of happenings, the accountability of specific individuals and agencies and the short and long-term consequences.

According to Lt General Sir Francis Tuker, GOC-in-C of the Eastern Command at Calcutta during the last eighteen months of British rule: ‘… the Hindu Police dominated the Intelligence Branch and the Criminal Investigation Branch who kept the government in darkness…’.

SUHRAWARDY’S ROLE AND OPPOSITION

The Oxford-educated Suhrawardy, a leading barrister, was initially associated with the Swaraj Party led by Chittaranjan (CR) Das (1870-1925), about whom he wrote:

‘The brunt of all elections in Bengal on behalf of the Muslim League had fallen upon me in my capacity as Secretary of the Bengal Branch of the All India Muslim League since 1937. Entering politics in 1920 ….. I was the Deputy Mayor of Calcutta with Deshbandhu C R Das as Mayor. He was the greatest Bengali, may I say Indian, scarcely less in stature than Mahatma Gandhi, I have ever had the good fortune to know. He was endowed with wide vision; he was wholly non-communal, generous to a fault, courageous and capable of unparalleled self-sacrifice. His intellectual attainments and keen insight were of the highest order. As an advocate, he commanded fabulous fees which he laid at the feet of his country. Towards the end of his days, he renounced his profession, devoted himself to politics ….. and died a pauper …. I believe with many that had he lived he would have been able to guide the destiny of India along channels that would have eliminated the causes of conflict and bitterness, which had bedevilled the relationship between Hindus and Muslims and which, for want of a just solution, led to the Partition of India and the creation of Pakistan’.

Even as Suhrawardy respected Jinnah, he harboured a complaint for not being appointed to the Muslim League Central Working Committee.

Liaquat Ali Khan and Mirza Abul Hassan (MAH) Ispahani were opposed to his inclusion, although he was only Muslim League Premier; Khwaja Nazimuddin and Ispahani represented Bengal in the Working Committee.

A veteran politician, a firebrand, Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani – more often called Maulana Bhashani (1880-1976) – has been credited ‘as much as any one man’ for instigating the 1969 uprisings in East Pakistan that culminated in the collapse of the Ayub Khan regime and the release of Mujibur Rahman and the others accused in the Agartala conspiracy case known as Mozlum Jananeta (Leader of the Oppressed), he had high regard for Mujib and wept when the news of the Bangabandhu’s assassination was conveyed to him.

Suhrawardy, Sheikh Mujib, and Bangladesh

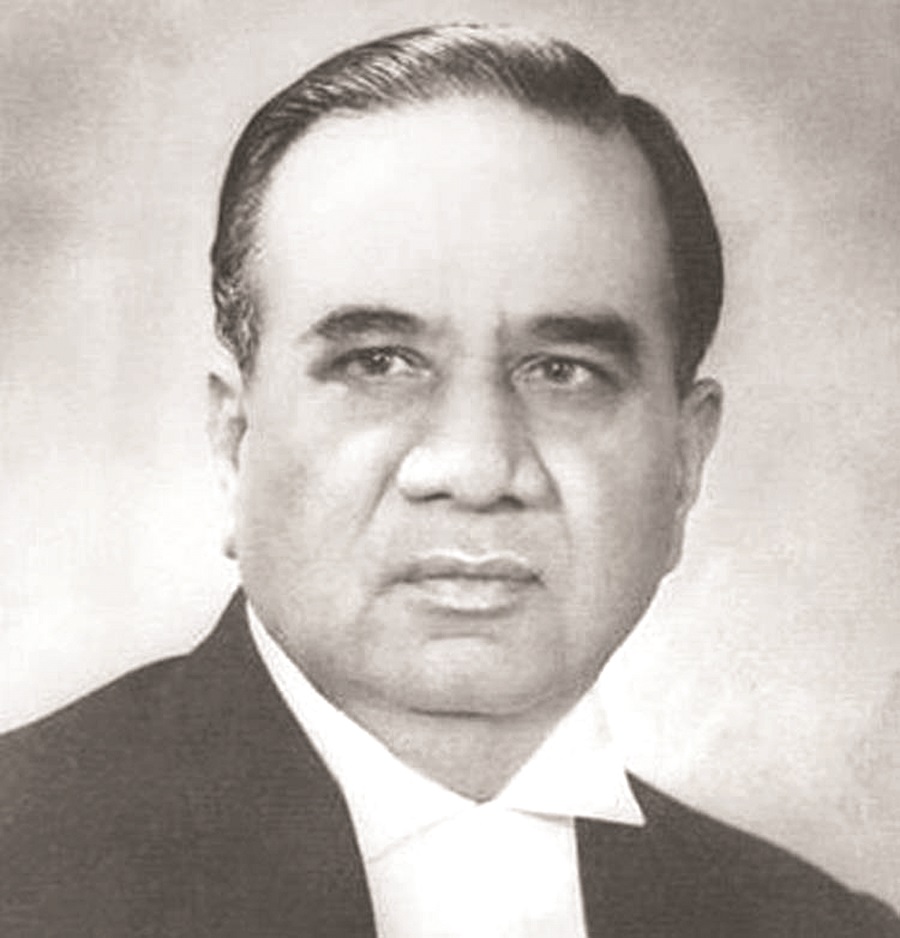

Suhrawardy was the political mentor of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and had, in 1956-57, been the fifth Prime Minister of Pakistan prior to a highly questionable dismissal by a soon-to-be discredited President, Iskander Mirza.

Records exist of the early contact between Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Suhrawardy, whom he (Mujib) appears to have first met around 1938 as a young student in Faridpur, East Bengal. The interaction developed into a relationship that impacted the post-Partition history of the Subcontinent.

Suhrawardy belonged to a rich, Urdu-speaking family of Calcutta; he spoke Bengali haltingly, whereas Mujib was a ‘son of the soil’ who could captivate an audience with his lyrical language. Unlike Suhrawardy, he had not been educated abroad and was ill-acquainted with Western liberal political thought. He was inflexible in negotiation and was not easily swayed by emotion.

Mujib saw in Suhrawardy the qualities that he himself lacked and this was, perhaps, echoed in Suhrawardy’s affection for him. He used to recall what he learnt from Suhrawardy whose death in 1963 devastated him and said: ‘Now when I think of him [Suhrawardy] in jail, I remember what he had told me then. Even in 20 years, he never veered from what he said that day. Indeed, from that day, every day of my life, I was blessed with his love …..’.

On Mujib’s first birthday after Bangladesh came into being (March 17, 1972), when the entire country was celebrating, huge multitudes had greeted him with flowers. That night, after the crowds had dissolved, Mujib (the Bangabandhu) took a mountain of flowers and placed them on Suhrawardy’s grave at the ‘Mausoleum of Three Leaders’ in Dhaka where he rests along with the redoubtable Sher-e-Bangla, A K Fazlul Huq (1873-1962) who needs no introduction and Khwaja Nazimuddin (1894-1964).

Suhrawardy’s legacy stays intact through his impact on Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s political philosophy. He is a ‘national hero’ in Bangladesh.

Reflecting on the emergence of a third successor-State to the British Indian Empire, the last Unionist Premier of the Punjab (1942-47), Sir Malik Khizar Hayat Tiwana (1900-75) stated, before his death in the United States: ‘I still think a Punjabi Muslim has more in common with a Punjabi Hindu or Sikh than with a Bengali (or any non-Punjabi really) and I think the separation of East Pakistan proved that’.

THE COMPLEX DYNAMICS OF BENGAL’S PARTITION

The National Unionist Party, formed in the Punjab province on a multi-community basis, viz. Muslims, Hindus (Jats), Sikhs and others, had luminaries like Sir Fazli Husain, Sir Chhotu Ram and Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan in its leadership. Staunchly opposed to the Partition of India, Khizar tried to convince the British government, as a last-ditch attempt, to accept his proposal for an independent Punjab, a separate entity to both Pakistan and India.

The English-educated middle class of Bengal, the bhadralok, saw the Partition as a measure to diminish their influence. The actual day of partition (16 October, 1905) happened to coincide with Raksha Bandhan and Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore (a future Nobel Laureate) urged that rakhis be tied, especially to Muslims, to emphasize inter-religious bonds and that Bengal was against division

That Pakistan was on the anvil was becoming clear in the early months of 1947. But this did not necessarily imply a partition of Bengal.

Around this time, a thought-process was evolving in the provincial units of the Congress and the Muslim League to identify ways for keeping a United Bengal. The matter was considered in the Labour Government of Clement Attlee, in the background of protection of British commercial interests.

The Governor was against the Partition of Bengal and had endeared himself to the ‘burrah sahibs’ of Calcutta with one of his first speeches when, alluding to his modest beginning on the railways, he said: “When you gentlemen were huntin’ and shootin’, I was shuntin’ and hootin’.”

Suhrawardy, a scion of one of Bengal’s most influential Muslim families, was an astute politician whose popular image was known to have caused discomfort to Jinnah and he appeared determined not to lose Calcutta to the Hindu-Muslim divide.

Endowed with skills of oratory, he enlisted the support of Hindu leaders of the standing of Sarat Chandra Bose (older brother of Subhas Bose) and Kiron Sankar Roy (leader of the Congress Party in the Legislative Assembly), as also of prominent Bengali Muslims, including the Finance and Revenue Ministers, the Secretary of the Bengal Provincial Muslim League, Abul Hashim, and heavy-weights like Ashrafuddin Chowdhury.

His cousin, Begum Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah (1915-2000) was a pioneer in public service in Pakistan, whose daughter, Princess Sarvath al-Hassan of Jordan is, therefore, his niece.

BENGAL’S PARTITION : CONGRESS VERSUS MUSLIM LEAGUE

In May, 1947, Sarat Bose and Abul Hashim called on Mahatma Gandhi to discuss the scheme of a United Bengal. The Mahatma gave a patient hearing but ultimately fell in line with Jawaharlal Nehru that the Congress would ‘agree to Bengal remaining united only if it remains in the Indian Union’. The Party President, Acharya Kripalani, reiterated the Congress’ insistence on the division of Bengal and the Punjab into ‘areas for Hindustan and Pakistan respectively’.

When the matter was raised with Mr Jinnah by Lord Mountbatten, he was told that he (Jinnah) would be happy if the proposal to create a separate, sovereign Bengal were accepted.

Stanley Wolpert (1927-2019), well-known American historian, confirmed that Mountbatten had asked Jinnah what he thought of Suhrawardy’s proposal and the reply was: “I should be delighted. What is the use of Bengal without Calcutta? They had much better remain united and independent. I am sure they would be on friendly terms with Pakistan”.

When Mountbatten enquired if Jinnah would wish Bengal to remain within the British Commonwealth, the latter said “of course, just as I indicated to you that Pakistan would wish to remain within the Commonwealth”.

Nehru and Sardar Patel were sceptical of Suhrawardy’s intentions and had veered to the view that he could eventually turn the tables by taking the whole of Bengal into Pakistan’s embrace.

THE IDEA OF A UNITED BENGAL PROVED STILLBORN

In Sarat’s opinion, it was the Congress that was more responsible for the collapse of the initiative than the Muslim League since Jinnah had supported the same.

VP Menon’s immediate predecessor as the Reforms Commissioner of the Government of India, Henry Vincent (HV) Hodson (1906-99), a Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, recalled that the ‘original plan for the Transfer of Power included an option for Bengal to decide on independence as a unit, but Nehru opposed it …..’.

VISION FOR A UNITED BENGAL: THE PLAN OF 1947

ON 27 April, 1947, the Bengal Premier, H S Suhrawardy (1892-1963) spoke to the Press in New Delhi articulating his firm opposition to a Partition of the province and making an impassioned case for setting aside religious differences in order to create an ‘Independent, undivided and sovereign Bengal’:

“Let us pause for a moment to consider what Bengal can be if it remains united. It will be a great country, indeed the richest and most prosperous in India capable of giving to its people a high standard of living, where a great people will be able to rise to the fullest height of their stature, a land that will truly be plentiful. It will be rich in agriculture, rich in industry and commerce and in course of time it will be one of the powerful and progressive States of the world. If Bengal remains united, this will be no dream, no fantasy”.

At this stage, a Plan was being outlined, in consultation with the Governor, Sir Frederick Burrows, stipulating that:

(i) Bengal would be a Free State that would decide its relations with the rest of India,

(ii) The Constitution of the Free State of Bengal would provide for election to the Bengal Legislature on the basis of a joint electorate and adult franchise, with reservation of seats proportionate to the population among Hindus and Muslims. The seats set aside for Hindus and Scheduled Caste Hindus would be distributed amongst them in proportion to their respective population, or in such manner as may be agreed among them. The constituencies would be multiple constituencies and the votes would be distributive and not cumulative. A candidate who got the majority of the votes of his own community cast during the elections and 25 percent of the votes of the other communities so cast, would be declared elected. If no candidate satisfied these conditions, that candidate who got the largest number of votes of his own community would be elected,

(iii) On the announcement by the British Government that the proposal of the Free State of Bengal had been accepted and that Bengal would not be partitioned, the existing Bengal Ministry would be dissolved. A new interim Ministry would be brought into being, consisting of an equal number of Muslims and Hindus (including Scheduled Caste Hindus), in this Ministry, the Premier would be a Muslim and the Home Minister a Hindu,

(iv) Pending the final emergence of a Legislature and a Ministry under a new Constitution, Hindus (including Scheduled Caste Hindus) and Muslims would have an equal share in the Services, including military and police. The Services would be manned by Bengalis,

(v) A Constituent Assembly composed of 30 persons, 16 Muslims and 14 non-Muslims, would be elected by Muslim and non-Muslim members of the Legislature respectively, excluding Europe ans.

The term ‘Free State of Bengal’ was intended to echo the legacy of the name of the Irish Free State.

EAST BENGAL VERSUS WEST BENGAL

A fatal weakness of the United Bengal Plan was its failure to mobilize tangible support from the Hindus of the province. Sarat Bose could not persuade them that a ‘disputed share’ in the governance of an undivided Bengal was preferable to partition and ‘undisputed power’. Only a few leaders stood behind him in a Party which he had once dominated but which was now controlled by men like Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy (an acclaimed medical expert) who owed their authority to Nehru and the Congress High Command.

In short, the Hindus decided to push for a truncated province of their own rather than risk the premiership of Suhrawardy whose record was very much under a cloud in the context of the Calcutta Killings. Sarat waited in vain for the Hindus of East Bengal to respond to his call. Many of them were by now reconciled to the bitter fact of separation and were in readiness to go westwards.

Despite his assertion that only a ‘section of the upper middle classes’ in West Bengal favoured division of the province, he could not, at the crucial moment, produce evidence to substantiate his claim that ‘the overwhelming majority of Hindus in East Bengal are dead against Partition’. On the contrary, even the Forward Bloc – the Party he had inherited from his brother, Subhas – withheld support.

Sarat Bose had also succeeded in alienating Subhas’ significant rank and file following. In November, 1945, when Calcutta’s student and left-wing organizations marched to Dalhousie Square to protest the harsh sentences handed out to the INA accused, he had distanced himself from what was to become a big uprising. This damaged his standing among his brother’s loyalists.

In Bengal, the Muslim community was concentrated in the countryside; Calcutta had a clear Hindu majority (73% of the population, according to the 1941 census) and a Muslim minority (23%). Most Muslims lived in North Calcutta, while Central and South Calcutta were almost exclusively Hindu, with a sprinkling of Europeans

The widely respected Syama Prasad Mookerjee (1901-53), then in the Hindu Mahasabha, was not far off the mark when he said that ‘Sarat Babu has no support whatsoever from the Hindus and he does not dare address one single meeting’.

The Bengal Boundary Commission – chaired, like the Punjab Boundary Commission, by Sir Cyril Radcliffe (later, 1st Viscount Radcliffe) – comprised two Hindus and two Muslims, namely, Justices CC Biswas (a later-day Union Law Minister), Bijan Kumar Mukherjea (a future Chief Justice of India), Abu Saleh Muhammed Akram, Chief Justice of the Dacca High Court (1947) and S.A. Rahman, ICS, who became Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Pakistan (1968).

Kiron Sankar Roy (he was, briefly, the Home Minister in Dr Bidhan Roy’s cabinet) passed away in 1949 and Sarat Bose the following year.

LEGACY OF CULTURAL TIES

The cultural and social affinities that underpinned and characterized everyday life in the two Bengals – as still obtaining at Partition – were sustained and nurtured, at least in part, by the affluent Hindu and Muslim feudal class that was composed of ‘absentee landlords’ living in Calcutta, Dhaka (and elsewhere) in considerable luxury and who were a dominating force.

The East Bengal Estates Acquisition and Tenancy Act, abolishing the zamindari system, came into force in February, 1950. The zamindars were to be paid compensation for the loss of proprietorship over their lands and were allowed to keep a maximum of thirty-three acres in their direct possession. Several zamindars went to Court against the legislation, claiming that it was a violation of the right to property and of the pledge made by Lord Cornwallis in 1793. The Government of East Bengal was defended by a legal team led by a well-known British barrister, DN Pritt (1887-1972) who came from London for the purpose. He was arraigned against senior Indian lawyers who argued for the other side in the Dacca High Court.

Pritt was a prominent member of the Labour Party from which he had been expelled in March, 1940 for supporting the Soviet invasion of Finland. He had earlier represented Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar and Shivaram Rajguru before the Privy Council, arguing that the Ordinance which had been used to set up a Special Tribunal to try them was ultra vires. The appeal was rejected. He successfully defended Ho Chi Minh against a French request for extradition from Hong Kong.

Suhrawardy, a scion of one of Bengal’s most influential Muslim families, was an astute politician whose popular image was known to have caused discomfort to Jinnah and he appeared determined not to lose Calcutta to the Hindu-Muslim divide

On the High Court Bench at Dacca was a Muslim ICS judge, originally of the Madras High Court, who was born in Ellore (now Eluru in Andhra Pradesh, India), had opted for Pakistan in 1947 and who rose to be Chief Justice of that country (1960).

PERSONAL BONDS AMIDST BORDERS

By and large, the Zamindars, alike of East Bengal and West Bengal, were serious litigants. In East Bengal, one of the oldest zamindaris, the Puthia Raj, was hit by its abolition. The Rajbari had been built as the palace of Maharani Hemanta Kumari Debi who died in 1942.

The Rajshahi Raj was the second largest zamindari in Bengal, next only to the Burdwan Raj. A member of the family, Jagadindra Nath Roy Bahadur (1868-1925) was known as the Raja of Natore and was succeeded by his son, Jogindra Nath Roy. Both father and son were avid cricket enthusiasts and promoters of the game; the Natore cricket team lasted until 1945 and rivalled that of the Maharaja of Cooch Behar.

The person-to-person contacts and links, often bordering on affection and in diverse fields like poetry (Tagore, Kazi Nazrul Islam) and popular music (RC Boral, Pankaj Mullick, Timir Baran) between the peoples of India and Bangladesh survive, even thrive.

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was close to Suvra Mukherjee (1940-2015), former First Lady of India – who was born in Narail, Jessore district, East Bengal – attended her funeral and said: ‘Bangladesh has lost a great friend and well-wisher with her passing away’.

THE BENGAL CONNECTION WAS A CEMENTING FACTOR

That the 1947 division of Bengal was different from that in the Punjab was, for instance, evident in April, 2020 when the death occurred in Kolkata of Dr Biplab Kanti Dasgupta, Assistant Director of Health Services, West Bengal due to coronavirus. He had moved to India after graduating from the Chittagong Medical College and was in the frontline of distribution of COVID-19 medical supplies to hospitals.

The life of Dr Dasgupta, hailing from Chattogram (Chittagong), exemplifies a bond that has luckily endured on both sides of the international border in Bengal.