The climate crisis requires urgent action, highlighted by 2024’s severe weather and record temperatures. But many countries, including India, are chasing development, often valuing economic growth at the expense of our natural environment

By Geeta Singh

- India’s commitment to Net Zero emissions by 2070 reflects growing public demand for decisive action against climate change

- India’s climate strategy features strong investments in renewable energy, growing solar and wind capacity, and low per capita emissions

- The Ken-Betwa River project threatens over 4,000 hectares of Panna tiger reserve. The Char Dham Road project may cost 508.66 hectares of forest

- Africa’s unprecedented mining surge poses grave risks to wildlife and ecosystems, driven by the growing renewable energy industry

IN the global race for modernization and economic expansion, nations, including India, have often placed development ahead of environmental preservation. This relentless drive has yielded substantial progress in infrastructure, industry, and technology, but at a significant environmental cost, manifesting in rampant deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and pollution.

However, this progress has come at a steep environmental price, particularly evident in India’s struggle to reconcile rapid economic growth with the need for ecological preservation. The country faces critical challenges, including deforestation, biodiversity loss, and pollution, which are exacerbated by the global dynamics of climate finance and the increasing frequency of extreme weather events.

As the world grapples with the repercussions of climate change, India stands at a crossroads. The nation’s commitment to achieving Net Zero emissions by 2070 reflects a growing public demand for decisive action against global warming.

ENVIRONMENTAL COST OF MODERNIZATION

A Reuters analysis of UN and OECD data reveals that wealthy countries like Japan, France, Germany, and the United States are profiting from a global initiative intended to aid developing nations in coping with climate change effects. These developed countries pledged to provide $100 billion a year to poorer nations to help them reduce emissions and handle extreme weather. However, they are channelling some of this money back into their own economies, contradicting the idea that they should compensate poorer natio

Wealthy nations have extended loans totaling at least $18 billion at market-rate interest. These loans include $10.2 billion from Japan, $3.6 billion from France, $1.9 billion from Germany, and $1.5 billion from the United States. This departure from the norm applies to loans for climate-related and other aid projects, which typically carry low or no interest.

Additionally, approximately $11 billion in loans—primarily from Japan—imposed a requirement on recipient nations to hire companies or purchase materials from the lending countries. Reuters found that at least $10.6 billion in grants from 24 countries, including India and the European Union, had similar conditions.

The year 2024 has seen a surge in extreme weather events globally, including floods, heatwaves, and droughts, as reported by the WMO. These events have profoundly affected health and livelihoods. While not all extreme weather can be directly linked to climate change, their increasing frequency and intensity are exacerbated by greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel combustion. The Northern Hemisphere experienced its hottest summer in two millennia in 2023, with 2024 on track to surpass this record.

May 2024 is set to break the temperature record for the 12th consecutive month, continuing the trend of the previous 11 months, which have all set new highs since the pre-industrial era. This sequence of record temperatures could extend into June, potentially marking two consecutive years of record heat for the month.

Both air and ocean temperatures have been breaking records for the past 12 and 13 months, respectively. The dominant influence of greenhouse gas emissions on global warming has surpassed natural climatic factors, such as the current El Niño event, contributing to the overall temperature rise.

The 2023 survey across India underscores a mounting concern over climate change, with an overwhelming 91% of respondents recognizing the reality of global warming. Conducted in the fall of 2023, the survey signifies a significant shift in public awareness of environmental issues.

The Indian populace is calling for urgent action, with 59% expressing grave concerns about the looming consequences of global warming. This apprehension is reflected in the 52% who attribute global warming to human activities, in contrast to the 38% who believe it is due to natural changes. The ‘Climate Change in the Indian Mind 2023’ report, initiated by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and CVoter, delves into the country’s climate change perceptions and attitudes.

The perceived risks of global warming are considerable, with 83% worried about wildlife, 82% about fellow citizens, 81% about future generations, 78% about their community, and 74% about their own families. More than half (53%) feel the impact of global warming, with a notable 34% considering relocation due to climate-related disasters.

The survey also highlights expectations of intensified natural disasters due to global warming, with predictions of increased heat waves (60%), species extinctions (57%), droughts (56%), cyclones (54%), famines (50%), and floods (46%).

The personal relevance of global warming is high, with 92% deeming it “extremely” (38%), “very” (35%), or “somewhat” (20%) important. This concern is translating into action, with 79% either already making significant lifestyle changes (25%) or expressing a willingness to do so (54%).

Wealthy countries like Japan, France, Germany, and the United States profit from a global initiative meant to help developing nations cope with climate change. Despite pledging $100 billion annually to aid poorer nations, they redirect some funds back into their economies, contradicting the intent to compensate poorer nations for the long-term pollution that caused climate change

There is a clear demand for more government action, with 78% advocating for stronger measures against global warming. Support for India’s commitment to achieving Net Zero emissions by 2070, as announced in the Panchamrit Declaration, is robust at 86%.

This survey from 2023 paints a picture of India’s profound concern for climate change, marking a pivotal moment for both individual and governmental dedication to environmental advocacy. As India navigates these challenges, the insights from the survey are essential for informed and decisive climate action.

CLIMATE COMMITMENTS

India, as the world’s third-largest greenhouse gases (GHGs) emitter, recorded emissions of ‘2,442 million tons’ of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) in 2020. While these figures are lower than those of China and the United States, India’s emissions have been on an upward trajectory, largely due to its focus on development and growth in various sectors.

To address this rise in emissions, India has pledged several Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement. The country has made strides in reducing its GDP emissions intensity by ‘24%’ from 2005 to 2016 and has maintained per capita emissions at ‘1.94 tCO2’, which is below the global average. Over ‘24%’ of India’s total installed electricity capacity comes from renewable sources, and when including large hydropower and nuclear energy, non-fossil fuels make up ‘38%’ of the installed capacity.

However, India’s increase in forest and tree cover, which contributes to carbon sequestration, has been modest, with an increase of only ‘5,188 km²’. This falls short of the ambitious target of a ‘680-817 Mt’ increase in carbon sinks.

Critics, including the Climate Action Tracker (CAT), argue that India’s NDCs lack ambition. CAT has rated India’s non-fossil fuel electricity capacity target of ‘40%’ as “critically insufficient” and its emissions intensity target as “highly insufficient” in the context of the ‘1.5°C’ global warming limit set by the Paris Agreement. To meet these stringent global standards, India needs to enhance its climate commitments and take more robust action to curb emissions.

Hence, India’s updated targets following COP26 include ambitious goals such as reaching a non-fossil energy capacity of 500 GW and fulfilling 50% of its energy requirements from renewable sources by 2030. By July 2021, our installed renewable capacity was 98.8 GW, up from 39 GW in 2015. While this is substantial progress, it remains short of the 175 GW target by 2022 under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The increase in greenhouse gases (GHGs) from burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and other human activities causes global warming and various changes in weather patterns, including more intense and frequent rainfall and flooding, more severe droughts, and more frequent and intense heat waves

CAT projections suggest that India is on track to meet its non-fossil fuel capacity targets, driven by the affordability of solar and wind power, increased investment in solar photovoltaics, and policy incentives for renewable energy manufacturing hubs and biofuels. However, this positive outlook is tempered by the country’s continued investment in fossil fuels.

HOW CLIMATE CHANGE INFLUENCES WEATHER

CLIMATE change significantly affects weather patterns, increasing the frequency, intensity, and unpredictability of extreme weather events. This essay explores the intricate relationship between climate change and weather, examining specific instances in 2024 and how climate change has influenced these events.

One of the primary drivers of climate change is the increase in greenhouse gases (GHGs) from burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and other human activities. These gases trap heat in the atmosphere, leading to global warming and various changes in weather patterns.

Warmer temperatures increase the rate of evaporation, putting more water vapour into the atmosphere. This can lead to more intense and frequent rainfall and flooding in some regions, while other areas may experience more severe droughts as the increased evaporation dries out soil and water sources.

The oceans absorb much of the Earth’s heat, and warmer ocean temperatures can intensify weather patterns, such as hurricanes and typhoons. These warmer waters can lead to more powerful and destructive storms. Global warming results in higher overall temperatures, which can lead to more frequent and intense heat waves. These heat waves can have severe impacts on human health, agriculture, and infrastructure.

The interplay of these factors causes shifts in weather patterns, leading to unpredictable and extreme weather events. As WMO climate expert Alvaro Silva noted, the timing and duration of extreme events are also changing, making it difficult to predict what constitutes “normal” weather.

HEATWAVES IN INDIA

In 2024, India and other parts of Asia experienced a severe heat wave with temperatures reaching 52.9 degree C (127.22°F). This heatwave led to numerous deaths and affected voter turnout during national elections. According to the World Weather Attribution (WWA) initiative, this heatwave was 45 times more likely due to climate change and was 0.85°C hotter than it would have been without human-induced climate change.

The extreme heat highlighted the vulnerability of populations in regions where many people work outdoors. Even small increases in temperature can have devastating effects on health and productivity in such settings.

FLOODS IN BRAZIL

Southern Brazil faced severe floods in 2024, particularly in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, resulting in over 100 deaths and the displacement of 1.5 million people. The floods caused significant damage, leading to discussions about relocating entire cities to avoid future disasters. Scientists have linked these floods to climate change, with studies indicating that human-driven climate change significantly increased the heavy rainfall that led to the flooding.

The vulnerability of the population, combined with inadequate infrastructure, exacerbated the damage caused by the floods. Effective flood management and improved infrastructure are crucial to mitigating the impact of such events.

TORNADOES IN THE UNITED STATES

The United States experienced a high number of tornadoes in 2024, with more than 100 tornadoes hitting the Midwest and Great Plains over four days. Tornadoes are challenging to attribute directly to climate change due to their localised nature and the complex factors that cause them. While climate change studies have not conclusively linked it to increased tornado activity, the unpredictability and variability of weather patterns could be influenced by broader climatic changes.

EXTREME WEATHER EVENTS

Extreme weather events have always been part of Earth’s climate system, even before significant human-induced climate change. Historical records show instances of devastating storms, floods, droughts, and heatwaves. However, the frequency and intensity of these events have increased in recent decades, correlating with the rise in GHG emissions and global temperatures.

Experts agree that while natural variability plays a role in extreme weather, climate change has made such events more likely and destructive. This increased risk underscores the need for robust climate policies and adaptation strategies to protect vulnerable populations and mitigate the impact of climate change.

CONTRADICTIONS IN POLICY

While India has made significant strides in renewable energy, it simultaneously continues to invest heavily in fossil fuels. The government aims to increase coal production to 1 billion tons by 2024-25, with coal-powered electricity generation growing at an annual rate of 6% since 2015. Coal capacity is expected to rise from 202 GW in 2021 to 266 GW by 2030, as evidenced by the recent auctioning of 40 new coal mines. This reliance on coal led to India’s last-minute objection to the “phasing out” of coal at COP26.

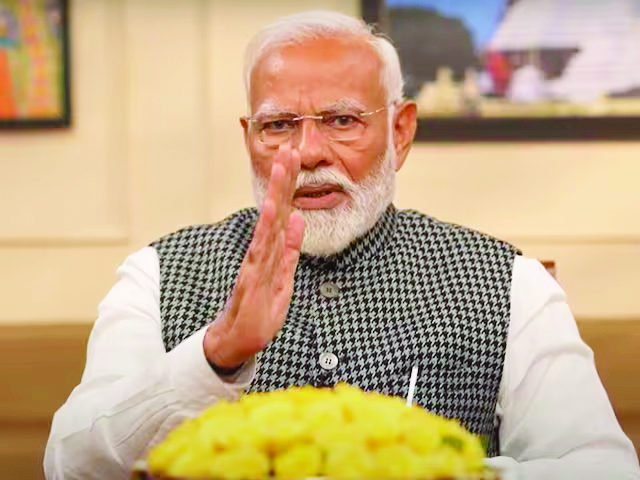

The decade-long tenure of Prime Minister Modi’s administration has seen significant achievements, yet its environmental policies cast a long shadow. Experts have identified these policies as a critical yet under-reported area of concern. While issues like unemployment and the farm crisis have garnered attention from the opposition and media, environmental concerns have largely remained unnoticed.

India’s ecological standing has significantly deteriorated over the past decade. The Environmental Performance Index (EPI), an international ranking system that measures the environmental health and sustainability of countries, ranked India lowest among 180 countries in 2022, with an overall score of 18.9. This represents a steady decline from 2014 when India was ranked 155th globally.

Balancing development while safeguarding the environment remains the biggest challenge for the Modi government. While the emphasis on ease of doing business is commendable, stakeholders believe it is coming at the cost of rampant environmental degradation.

Perhaps the most damaging decisions are the proposed changes to the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process. The draft EIA notification issued in March 2021 proposes mechanisms to legitimise actions currently listed as violations, such as projects that start construction without a valid clearance. It also reduces the public consultation period from 30 to 20 days, making it difficult for people to verify EIA reports.

RELAXATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL NORMS

Within weeks of taking office in 2014, the Modi government lifted the ban on setting up factories in critically polluted industrial belts and eased environment clearances for mid-sized polluting industries. The number of independent members in the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL) was reduced from 15 to just three, leading to almost all industrial projects being approved.

In December 2017, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) allowed thermal power units to release pollutants in violation of 2015 limits. By 2018, 15 of the world’s most polluted cities were in India.

The Char Dham Road project in Uttarakhand has been criticised for environmental neglect and indiscriminate forest cutting. Experts estimate a loss of 508.66 hectares of forest area and 33,000-43,000 trees for road widening.

High-altitude villages like Tokyo and Asrang experienced a transformation. Terraces full of apple trees now bring colour and aroma, attributed to climate change. However, these villages have also become guinea pigs in a failed three-decade experiment of neo-liberal globalisation, influenced by mega-corporations involved in drafting

the Kyoto Protocol

The proposed Ken-Betwa River linking project in Madhya Pradesh threatens to destroy over 4,000 hectares of the Panna tiger reserve, impacting critically endangered species.

Government proposals for large-scale development in these ecologically sensitive areas have raised environmental concerns. Projects include a mega trans-shipment terminal, an airport, and extensive land ownership changes, risking severe ecological impacts.

India’s quest for modernization is turning old-world spiritual oases into modern, glitzy destinations, with devastating environmental consequences. There is an immediate need to reassess environmental policy and introduce measures to balance development with ecological preservation.

CHALLENGES TOWARDS COMMITMENT

India’s climate strategy has notable strengths, including significant investments in renewable energy and a growing capacity for solar and wind power. The country’s low per capita emissions also demonstrate its relatively small carbon footprint compared to global standards. However, weaknesses persist, particularly in the ambitiousness of its NDCs and the conflicting investments in fossil fuels.

To maintain momentum and meet its updated targets, India must adopt bold measures and possibly reconsider some recent policies that counter its climate commitments. Clear and actionable plans for achieving these targets are essential, as is the need to address ambiguities in the commitments made at COP26.

India’s journey toward sustainable development and climate resilience is marked by significant achievements and notable challenges. The increasing frequency of extreme weather events globally underscores the urgency of robust climate action. While India has made commendable progress in reducing emissions intensity and expanding renewable energy, more ambitious targets and a decisive shift away from fossil fuels are necessary. Balancing development with environmental sustainability requires continuous innovation, strong policy frameworks, and unwavering commitment to global climate goals. Only through these efforts can India and the world hope to mitigate the impacts of climate change and secure a sustainable future for all.

Africa, much like India, is amid a mining surge that has not been seen before, bringing with it grave risks to its wildlife and ecosystems. This surge is marked by a ramp-up in mining operations, especially in areas that have not been mined before. Although Africa is home to roughly 30% of the planet’s mineral reserves, it has only tapped into less than 5% of these resources, suggesting a vast potential for sectoral expansion.

The burgeoning renewable energy industry is poised to accelerate mineral extraction as the need for minerals essential to renewable energy technologies escalates. Africa’s vast biodiversity, which includes about one-sixth of the world’s remaining forests and one-quarter of all mammalian species, many of which are primates, faces imminent danger. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List indicates that around 67% of primate species are at risk, with 73.1% of African primates endangered and 42% witnessing population declines.

The juxtaposition of Africa’s mineral boom and India’s net-zero commitment highlights the complex interplay between economic development and environmental sustainability. Africa’s mining expansion threatens its rich biodiversity, calling for balanced development strategies that protect ecological integrity. Meanwhile, India’s mixed approach to international climate negotiations, combining ambitious net-zero targets with a pragmatic stance on fossil fuels, reflects the broader challenge of reconciling developmental aspirations with climate action. Both regions must navigate these challenges carefully to achieve sustainable growth while mitigating the adverse impacts of climate change.

LESSONS FROM HISTORY

“The environmental problems of developing countries are not the side effects of excessive industrialization but reflect the inadequacy of development. While rich countries may view development as the cause of environmental destruction, for us, it is essential for improving living conditions, providing food, water, sanitation, and shelter, and making deserts green and mountains habitable.” These words, spoken by former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi at the UN Conference on Human Environment in Stockholm on June 14, 1972, resonate today as the planet faces worsening environmental challenges. Over the past 52 years, the vision Indira Gandhi outlined has not materialised, with significant environmental degradation affecting billions worldwide.

Dr Gyan Chand, a distinguished economist from the twilight years of British rule in India, highlights the socio-economic and ethno-cultural oppression faced by the masses in his book ‘Teeming Millions’. The affluent nations often address environmental crises with grandiose pledges that remain unfulfilled, exacerbating the plight of developing countries.

Balancing development while safeguarding the environment remains the biggest challenge for the Modi government. While the emphasis on ease of doing business is commendable, stakeholders believe it is coming at the cost of rampant environmental degradation

Established in 1968, the Club of Rome emerged as a global think tank committed to resolving international political issues. Its seminal work, ‘The Limits of Growth’, published in 1972, emphasised the finite nature of Earth’s resources and warned of the rising costs of resource extraction due to industrial growth. As we mark its 50th anniversary, it’s clear that while some forecasts were exaggerated, its warnings about carbon dioxide emissions and climate change were accurate.

KYOTO PROTOCOL

A decade ago, high-altitude villages like Tokyo and Asrang experienced a transformation. Terraces full of apple trees now bring colour and aroma, attributed to climate change. However, these villages have also become guinea pigs in a failed three-decade experiment of neo-liberal globalisation, influenced by mega-corporations involved in drafting the Kyoto Protocol.

The Kyoto Protocol, adopted in 1997, committed industrialised countries to stabilise greenhouse gas emissions. It placed a heavier burden on developed nations under the principle of “common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities”. Despite its intentions, the protocol faced challenges, with major emitters like the USA and Canada withdrawing.

The Conference of the Parties (COP) is the main decision-making body of the UNFCCC, assessing measures to limit climate change. Despite significant progress at COP23 and COP24, the global temperature has already risen 1 degree Celsius since 1880, and achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement remains challenging.

BIG POLLUTERS AND CLASS STRUGGLE

Jeremy Corbyn, former leader of Britain’s Labour Party, frames the climate crisis as a class struggle. He criticises major polluters and extractive industries for perpetuating climate change, citing historical examples like the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s (AIOC) actions. AIOC later became BP, which continues to pump hundreds of millions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere at sites from the Gulf of Mexico to the Caspian. And much of the world’s fossil money is handled by City of London financial institutions which specialise in managing oil profits. Corbyn’s successful 2019 resolution declaring a ‘climate change emergency’ in the UK Parliament underscores the urgency of global action.

US Senator Bernie Sanders emphasises the existential threat of climate change, advocating for a clean energy economy that addresses climate challenges and creates job opportunities. Sanders’ vision highlights the potential for positive change amidst dire circumstances.

The journey towards balancing development and environmental sustainability is fraught with challenges. Historical insights and contemporary political actions offer valuable lessons. It is imperative to reassess global environmental policies and commit to sustainable practices that protect the planet for future generations.