Tracing its roots back to the colonial era, the Indian Civil service has evolved from an instrument of imperial control to a cornerstone of democratic governance.

By Dr Mohan Kanda

- Civil services are appointed civil servants working for governments, not parties, ensuring continuity across political leadership changes

- In democracy, civil services’ authority has rightly shifted to elected representatives, with the process being smooth and harmonious

- In 1829, the British East India Company founded the East India Company College to train administrators, starting the ‘Indian Civil Service’ exams

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the first Home Minister, and considered as the ‘Father of Modern All India Services,’ referred to the civil services as the ‘steel frame’ of India

THE National Civil Services Day was observed on 21 April this year, as it is every year. On this day, civil servants rededicate themselves to the cause of public welfare and renew their commitment to excellence. It was on this day in 1947 that Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the first Home Minister of Independent India and considered as the ‘Father of Modern All India Services,’ referred to the civil services as the ‘steel frame’ of India while addressing probationers of the Indian Administrative Service. Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of India during the British Raj, laid the foundation of the civil services in the country. His successor, Charles Cornwallis, who modernised and rationalised it, is known as ‘the Father of Civil Services in India.’

‘Civil services’ is a collective term for career civil servants who are appointed, rather than elected, to work for and answer to governments, not political parties. Their institutional tenure survives transitions of political leadership, acting as a buffer between varying political leadership. The UK, New Zealand, Canada, Finland, and Australia are best known for the effectiveness of their civil services.

ORIGINS & HISTORICAL FOUNDATION

The origin of the modern meritocratic civil service can be traced back to Imperial China, where the concept of a civil service first arose. The system, based on merit, was designed to select the best people for the administration. Following a request by many Englishmen in the 18th century for adoption of something similar for England, the Northcote Trevelyan Commission was constituted to make appropriate recommendations. In its report, the Commission recommended that recruitment should be on the basis of merit through a competitive examination, that candidates should have a solid general education to enable inter-departmental transfers, that recruits should be graded into a hierarchy and that promotion should be through achievement, rather than “preferment, patronage or purchase”. A permanent, unified and politically neutral civil service was introduced, in 1870, as Her Majesty’s Civil Service. The model remained stable for a hundred years. A tribute to its success in removing corruption, delivering public services and responding effectively to political change.

The origin of the modern meritocratic civil service can be traced back to Imperial China, where the concept of a civil service first arose. The system, based on merit, was designed to select the best people for the administration. Following a request by many Englishmen in the 18th century for adoption of something similar for England

The British East India Company established the East India Company College to examine, select and train administrators of the company’s territories in India. Examinations for the ‘Indian Civil Service’, a term coined by the Company, were introduced in 1829.

The authority, and power, vested in the civil services have, over time, shifted to the elected representatives of the people, as they should, in a democracy. By and large, the process has been smooth and harmonious. One, in fact, looks forward to the process encompassing functions such as the maintenance of law and order, as in the case of countries such as the USA. The transition, however, has not been without its concomitant Issues. While people’s representatives often complain of undue resistance by civil servants to their suggestions and orders, officials, in turn, complain of political interference in administrative issues. Not all political leaders are scrupulously honest, nor are all government officials honest and sincere. This has led to an inevitable tussle between politicians and civil servants, mostly on ideological issues, but, on occasion, fuelled by selfish motives.

AUTHORITY & ACCOUNTABILITY

Fortunately, there has been no dearth of civil servants who have held their own in trying situations. Names of such great personalities as T N Seshan, S R Sankaran and B D Sharma come to mind in this context. While by no means claiming to belong to that class of civil servants, I was, in my own humble manner, able to hold my own in moments of crisis while working with a number of great personalities, including many Union Ministers, Chief Ministers, Governors, and the Vice President of India. My ability to resist and overcome temptation, as well as fear, was repeatedly tested and, fortunately, stood established.

Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of India during the British Raj, laid the foundation of the civil services in the country. His successor, Charles Cornwallis, who modernised and rationalised it, is known as ‘the Father of Civil Services in India’

Ashok Gajapathi Raju, from the royal family of Vizianagaram in Andhra Pradesh state, is one of the most cultured, suave, and likeable political leaders I have worked with. Once, when he was Minister for Excise and I was the Commissioner of that department, we had a discussion about the authority to transfer and post officials. Drawing a parallel from the game of cricket (he was at that time the President of the Andhra Cricket Association and I was the President of the Hyderabad Cricket Association), I told him that a Minister ought to be like the Manager of a cricket team, while the Head of the Department should be the Captain. The Manager would be well within his rights to tender advice to the Captain before the game and after. However, it would not be in the interest of the game for the Manager to keep telling the Captain what to do about field placement, batting order, and bowling changes while the game is in progress. After all, freedom of action is a prerequisite for accountability.

The issue cropped up again when I was the Collector of Guntur district in that state. The Minister in charge of the Panchayati Raj department kept ordering transfers of teachers and other officials within the district. When I brought this to the notice of the Chief Secretary, A Krishnaswamy, he told me to write a letter to him, which, typical of him, he dictated to me himself ! “Transfer is an instrument of control,” the letter read, and authority and accountability should reside at one level; which is precisely the reason why officials are expected to handle transfers and postings and be held accountable for their actions. If authority is reposed at one level and accountability expected from another, the letter went on to say, the system simply will not work.

CIVIL SERVICES BOARD AND BEYOND

On another occasion, I happened to call on Krishnaswamy Rao Sahib, the Cabinet Secretary to the Government of India. Rao Sahib was in the process of giving shape to the concept of the Civil Services Board (CSB). Years later, the Supreme Court of India while dealing with a case before it, issued a direction, to the Central and State governments, to constitute such Boards. The whole idea is to insulate the process of transferring and posting officials from political interference and other vested interests. Unfortunately, however, I found, during my tenure in the Government of India, that when Secretaries to departments were asked to bring their views to meetings of the Board, they took to the practice of circulating internal notes, within their departments, to their Ministers and coming to the meeting, armed with Ministerial views thus defeating the purpose of the system.

I also recall, in this context, an unforgettable character whom I encountered in my service. Narasaiah Naidu, as a Deputy Tehsildar at Rajampet, in Kadapa district of the then Andhra Pradesh state, was famously known for having given chase to a village officer running away from his Court, during the proceedings of a criminal case. As that amusing incident had taken place for want of a law, authorising revenue officials to arrest errant village officers, what is known as the ‘Revenue Malversation Regulation’ had to be brought in. Narasaiah was, again, the Tehsildar of Chirala taluk when I was the Sub-Collector of Ongole division of Prakasam district. As I was conducting the annual inspection of the Tehsil Office, an MLA sent in a chit with a request for an interview with the Tehsildar. The casual contempt, with which Naidu crumpled the chit, and threw it away, telling the attender who brought it in to tell the MLA that he was busy with the Sub Collector‘s annual inspection, had to be seen to be believed!

CHECKS & BALANCES

In 1969, VV Giri, the then Vice President had resigned from office to run for President. With the President’s position vacant (on account of the demise of the then President, Zakir Hussain), and the Vice President not there, Justice Hidayatullah, who was then the Chief Justice of India, was sworn in as the ‘Acting President’, in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution of India. When it was suggested to him that he be described as the ‘acting’ President, Hidayatullah pointed out that, as the Constitution provides that “there shall be a President of India…,” and he was occupying that post, he was, therefore, the President of India, and not the ‘Acting’ President. This position was accepted at that time. In 1982, as an extension of the earlier precedent, the question was whether we should ask for a seal that read “President of India”. I, as the Secretary to the Vice President then, advised him that, this time around, there was a President who was only unable to discharge his functions. The Constitution provides that when the President is unable to discharge his functions the Vice President will do so. Hence the Vice President can only ‘act’ as the President. Advice was sought of Peri Sastry, the then Law Secretary of India, who confirmed the stand I took. The Vice President appreciated the position and possible embarrassment was averted.

DEALING WITH PROTOCOL

In 1981, as Secretary to the Vice President of India, I accompanied Vice President Justice Hidayatullah on an official visit to Canada Dr Gurdial Singh Dhillon was India’s High Commissioner in Canada. Our itinerary took us on a visit to Chateau Montebello, near Quebec, the venue of a G7 summit held earlier and attended, among others, by Ronald Reagan, (US President), Francois Mitterrand, (French Premier), Pierre Trudeau, (Canadian Prime Minister) and Margaret Thatcher, (British Prime Minister). Enroute we were crossing a river on a punt. The High Commissioner walked up to the car in which I was travelling, peeped in and asked “who is the Secretary to the Vice President?” I was in between two other people and raised my hand, much like a pupil in a classroom.

The central government, recently, took to limited open market recruitment, to posts, at the crucial level of Joint Secretary, apparently convinced that it was a step that would improve both quality and efficiency

“You appear ignorant of the fundamentals of protocol,” he said, and walked away. I jumped out of the car, smoke coming out of my ears, wondering what I had done wrong. When I asked him what the matter was, Dhillon said that, as I might have noticed, in the carcade from Ottawa to Quebec, his car was trailing the Canadian Protocol Car which, in turn, was behind the Vice President’s car. He was agitated that he was unable to fly the Indian flag on his car since the Canadian Protocol vehicle was ahead of his car. Firmly, but politely, I replied that, while I had a limited knowledge of these matters, there were two things to be noted. Firstly, we were in his jurisdiction – in a country to which he was our High Commissioner – and it was the High Commission which had put the car plan in place, in consultation with the Government of Canada. The Vice President’s staff had no role. Secondly, just as in a parade, (where the parade commander alone salutes, while the rest of the parade comes to attention), in a carcade the leading car, alone, flies the flag. The Vice President’s car was flying two flags, as is the custom – the Canadian and the Indian as required by the rules of protocol. Dhillon appeared unconvinced, and had perhaps protested to the Vice President and also reported the incident to the Government of India, which was only made known to me indirectly at a later date. However, I was neither called upon to furnish my explanation subsequently, nor was my understanding of the protocol questioned. Sound homework with clarity and confidence, clearly, comes in handy in handling of the delicate and sensitive matters.

LEGISLATIVE CHALLENGES

In 1983 in Andhra Pradesh, NT Rama Rao was the new Chief Minister. I was Joint Secretary in the Chief Minister’s Office. A resolution had earlier been passed by the State Legislative Assembly recommending the abolition of the State Legislative Council (LC). Every LC is constituted through a resolution of the Assembly, subsequently approved by Parliament. The Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, processes the matter. The same procedure is followed for its abolition.

The budget of the State Government had to be passed. The provisions of the Constitution of India lay down that if a State has two houses, the lower house first passes the budget and the upper house endorses it and returns it. What the upper house says about the budget is not as important as the need for it to consider and return it. While the State Assembly had passed the resolution abolishing the LC the Government of India had not processed its approval yet, thus creating an anomalous situation with reference to the LC in Andhra Pradesh. Not passing a year’s budget had never happened in any State until then.

A civil servant needs to cultivate the habit of standing his ground when matters of principle are brought into question. Many safeguards are available at several levels to encourage civil servants to stand up to their rights when their political masters make demands not consistent with the imperatives of the public interest and the spirit of the laws and rules in force

A suggestion was made to promulgate an ordinance, which also would have been an unprecedented step. The Constitutional validity of such a course of action was also not certain. A financial emergency or the collapse of the constitutional machinery are the two crises no state government wants. At that point, I made a suggestion to NTR that the practical and constitutionally safe method would be to summon the LC (technically still in existence). The opposition parties may embarrass him by boycotting his call, since his Telugu Desam Party (TDP) had no members in the LC yet. I pointed out that the numbers of the Assembly were such that TDP could have nine members in the LC, and nine was the quorum of the LC. Surely, the nine TDP members, (who needed to be nominated yet, and would be members only for a short while until Parliament approved the proposal for abolition of the LC), would attend the LC.

When the budget was tabled in the LC, that house would be formally in order in terms of the requirement of quorum. Because of the lack of majority the budget would not be endorsed, but that was not necessary. The LC only needed to consider and return the budget to the Assembly. Thus was passed the Budget of Andhra Pradesh in 1983. A possible emergency in the State was avoided by using the extant law and procedures although the solution may not have been politically palatable.

UPHOLDING PRINCIPLES

A civil servant needs to cultivate the habit of standing his ground when matters of principle are brought into question. Many safeguards are available at several levels to encourage civil servants to stand up to their rights when their political masters make demands not consistent with the imperatives of the public interest and the spirit of the laws and rules in force.

In 1989-90, as Secretary, Food and Agriculture, Government of Andhra Pradesh, I had a Minister who took a stand which, according to me, was not quite in keeping with the public interest. When my request for reconsideration was declined, I sought permission from the Minister to seek a review of his orders, in an appeal to the Chief Minister. And the Minister, on shaky ground even to begin with, promptly changed his mind. The Secretariat Business Rules (BRs) which had the force of law, when read with article 311 of the Constitution of India provided, in more than adequate measure, methods by which unwarranted interference with the attempt to do what is right could be dealt with.

A matter relating to the agricultural marketing department once came up for consideration. Two courses of action had been presented by the Commissioner of Marketing, the head of the Agriculture Marketing department. After detailed analysis I had concluded that one of the alternatives was the just and fair route to take, and the other fraught with potential for attracting criticism as being discriminatory. Accordingly, I submitted the case to the Minister, duly recommending the alternative I preferred together with full justification therefore. Sadly, not only was the Minister on the take, but quite brazenly so. He chose the second alternative; perhaps he had been gotten at by the party concerned. While I was debating in my mind about the manner in which to tackle the impasse, a notice was received from the High Court. One of the parties (in whose favour the decision would have been taken had my recommendation carried the day) had approached the High Court. The court desired that the government decide the matter and apprise it of the result.

MINISTERIAL CONFLICT

What the Minister was, as I have mentioned, not quite what I had recommended. Still, it was neither illegal, immoral, nor contrary to the stated policy of the government. Had that been the case, I could have taken refuge in the provisions of the Business Rules which provided for reconsideration and review. I therefore left the matter there, but not without making one more attempt – albeit unsuccessful – to convince the Minister that what he was doing would not stand up to external scrutiny by, for instance, by a court of law. Government orders were issued in pursuance to the decision of the Minister. They were promptly challenged again in the High Court. The arrangement in the Andhra Pradesh Secretariat at that time was that any affidavit to be filed in defence of a government decision would be seen and approved by the secretary concerned (not by the Minister, as the secretary was the respondent impleaded in the proceedings in the court). In the instant case the question was whether the decision was to be defended by the department, although, as a matter of fact, its advice against it had been overruled. This is where the mischief of the system comes into play. What had to be justified in the court of law was the decision of the government as an entity. The fact that the Minister differed with the recommendation made to him was a purely internal issue. The decision of the government had been called into question. It was that decision that had to be defended now.

Not all political leaders are scrupulously honest, nor are all government officials honest and sincere. This has led to an inevitable tussle between politicians and civil servants, mostly on ideological issues, but, on occasion, fuelled by selfish motives

Needless to say, the attempt made to draft a counter affidavit, to meet the grounds on which the government order had been assailed, proved to be a complicated task. After all, whatever allegations the petitioner was making were precisely those against which the Minister had been forewarned. I could, in fact, hardly have agreed with the petitioner more! Despite the most sincere and impartial effort we made to justify the decision of the Minister, the judge saw through the shabby cover up being attempted by the department and remarked that something was amiss and the court intended “to get to the bottom” of the issue.

CURRENT FILES AND NOTE FILES

Government files generally comprise two parts. One is the “current file” in which are placed the currents or papers relating to the correspondence on the subject. The other is the ‘note file’, in which examination of the issues concerned takes place within the four walls of the Secretariat, through notes made by the various functionaries concerned. It also contains the views expressed by various functionaries, of the departments involved in the exercise, together with their recommendations and the final decision, in the shape of the orders of the Minister in charge of the department. As a matter of general practice, note files are not produced in courts of law unless specifically required. Finally the judge, who had all along suspected precisely what had happened, called for the note file. One look at the noting was enough for him to understand the situation. The court ruled in favour of the petitioner and set aside the order of the government. Although it went against my grain I had performed my duty sincerely. Justice had prevailed, thanks to the doctrine of separation of powers and the system of checks and balances, which had kicked in to save the day.

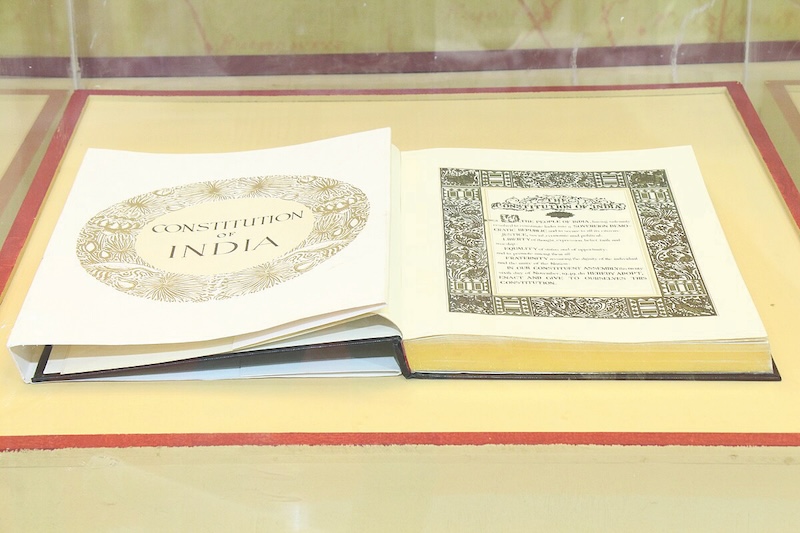

The extraordinary protection provided to civil servants by the Constitution of India should inspire them to hold their heads high and perform their duties without fear or favour. No country in the world has a constitution that makes a specific mention of its civil services

I recall a similar case in which the court had issued a direction to the government and, upon being moved again, ordered implementation of its earlier direction within a specified time. I had resubmitted the case to the then Minister who had been resisting implementation of the direction given earlier. He had kept the case with him and the deadline prescribed by the court expired. The court then proceeded to order the issue of a notice for contempt. It was hardly proper for me to explain the actual position to the court. On the other hand it was I who would have been hauled up for contempt, and possibly been jailed, for not implementing the court’s orders. Once again the court demanded production of the note file and, upon understanding the stalemate, issued a notice of contempt to the Minister in turn. Unwilling to face the dire consequences in store for him the Minister backed out and the matter was settled.

The point I am trying to make is that our system has many inbuilt safeguards and there is really little to be said in defence of those who cite political interference as the cause for their apparent helplessness.

PRIDE & CONCERNS

As India celebrates ‘Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav’, a quick inward look presents a bit of a mixed bag. On the one hand, the historic non- violent freedom movement, which freed the country from colonial rule, is a matter of pride and satisfaction. As is the fact that the democratic form of governance, chosen by our forefathers, has taken firm and deep roots. The rainbow of revolutions, green, white, yellow and blue in the food grains, milk, oilseeds and fishery sectors, ushering in an area of food security, in a country earlier plagued by famines and a so-called ship-to-mouth existence, was no small achievement. The exemplary functioning of constitutional and statutory institutions, such as the Supreme Court of India, the Election Commission and the Union Public Service Commission, that has earned laurels for the country internationally also warms the cockles of one’s heart. But, on the flip-side, scourges such as poverty, disease, squalor, fear, lack of access to quality education, and health continue to haunt millions. Add to that fact that the despicable practices of trading in children and killing of women in the name of honour and farmers committing suicide on account of economic distress rage unabated, and one is hardly surprised at the woefully low rank of the country in the Human Development Index prepared by the UNDP. And, in that kind of a situation, it is, indeed, unfortunate to see the central and state governments persisting with lopsided priorities. The continued neglect of important sectors and inequitable distribution of the benefits so far achieved across sections of people and regions of the country is really a worrisome thing. Corruption has pervaded in many walks of public life, even those generally accepted as Holy Cow professions. Political leaders, civil servants, doctors, engineers, chartered accountants and lawyers, even judges have been tried, convicted, sentenced and jailed. The consequent, and enormous, trust deficit created in the minds of the public, is truly frightening.

A great task of national building awaits, in which everyone will have a role to play, with civil services, in particular, having a significant contribution to make.

DISTINGUISHED PREDECESSORS

Thanks to the courage and boldness of many distinguished civil servants of the past, a firm foundation has been laid upon which the present generation of civil servants can build the structure of the future. Sagacity and wisdom are important attributes the political leaders and administrators of today need, if their actions are to prove equal to the hopes and aspirations of the people.

The opportunity, which the civil services offer, to use horizontal and vertical networking connections (through the parent cadre and the batch of allotment), to help those in need, is truly remarkable. The ‘esprit de corps’, or the feeling of pride shared by the members of an All India Services need to be leveraged, as a feature that can act as a great facilitator of action meant for the good of others.

Being a member of one of the All India Services, however, is not the most coveted of professions. As Oscar Wilde said of George Bernard Shaw, one may have no enemies, but may be intensely disliked by friends! An understandable feeling, in many ways, as the mere passing of one examination, scoring a few more marks than others, puts the civil servant in a position, particularly in the district, of the being the ‘numero uno’, the achievements and accomplishments, and claim to fame, of many persons belonging to other important careers, such as political leaders, the judiciary, members of other civil services, industrialists, academicians and scientists notwithstanding.

DEVELOPMENT IN GOVERNANCE

Among the more forward-looking features, that has characterised recent developments in governance, are the emphasis on transparency, prudence and accountability. The coming into being of the Right to Information Act, is an example of that. There can however, be too much of any good thing, and so is the case with transparency. The concept can, on occasions, be carried too far. Televising the proceedings of the houses of Parliament, and of legislatures in the states has, for example, often led to posturing by the members who have begun to speak what they believe their constituents would like to hear, rather than what is in their mind. The concept of transparency and, consequently, that of accountability, should therefore result in creating a sense of responsibility in the administration, rather than one of fear or, what is worse, paralysis.

As India celebrates ‘Azadi Ka Amrit Mahotsav’, a quick inward look presents a bit of a mixed bag. On the one hand, the historic non- violent freedom movement, which freed the country from colonial rule, is a matter of pride and satisfaction

Above all, as the late M R Pai (a civil servant of yesteryear from the Andhra Pradesh cadre) once put it, civil servants need always to remember that they are public servants, not government officials; instruments of governance, not tools in the hands of politicians. It is the citizens of India whom they exist to serve; their satisfaction they need to strive for, and their ire they should guard against. No one else matters.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROTECTION

The extraordinary protection provided to civil servants by the Constitution of India should inspire them to hold their heads high and perform their duties without fear or favour. No country in the world has a constitution that makes a specific mention of its civil services. There is absolutely no need, therefore, for the civil servants to bend, much less crawl. LK Advani famously observed, during the days of national emergency, in the 1970s. They only have to ensure that their actions do not tantamount to colourable exercise of power, that they are not arbitrary, discriminatory or mala fide.

The manner in which both the Central government and State governments blow hot and cold, in their attitude towards the civil services, has caused both gratification and amusement

Neither fear nor temptation, therefore, need pose a threat to the integrity of a civil servant. The service calls neither for the outstretched hand, nor the hung head. “Ehl-e-dil hai hum chashm-e-karam se bhi beniyaz” as the famous poet, Sahir Ludhianvi, wrote. Also, while it may not compare with the highest paid jobs in the country, the perks and emoluments are more than adequate for a civil servant to live a life of comfort, if not luxury. For example, having started at a salary of 400 rupees a month way back in 1968, I now draw a pension in excess of a lakh and half of rupees a month. The civil servant is also looked up to in society and, at an early stage in life, is trusted with enormous authority and power, especially to deal with issues relating to the welfare of the underprivileged. And no other career can offer the kind of variety, or challenges, which the civil service offers.

FLUCTUATING STANCE

The manner in which both the Central government and State governments blow hot and cold, in their attitude towards the civil services, has caused me both gratification and amusement. The state governments, on the one hand, continuously demand a large quota for promotions from the state services to fill vacancies in their IAS cadre. On the other hand, they refuse to release IAS officers to serve in the Centre, when requested to do so. The central government, recently, took to limited open market recruitment, to posts, at the crucial level of Joint Secretary, apparently convinced that it was a step that would improve both quality and efficiency. But, at the same time, it also circulated a draft amendment to the rule pertaining to releasing IAS officers for serving in the centre, which would have the effect of commandeering them to serve in the Central government. The Service can take comfort in the fact that the glitter attached to it is not yet a thing of the past!

I always kept in mind the inspiring words of Atal Bihari Vajpayee “Ooncha Mastak, Ubhara Seena/Jeena ho to Aisa Jeena”. During the classes I have been taking, over the last 10 years or so, for civil service aspirants I have also emphasised the importance of my three fold mantra, namely, physical fitness, mental alertness, and emotional stability

LITIGATION FOR REFORM

I always kept in mind the inspiring words of Atal Bihari Vajpayee “Ooncha Mastak, Ubhara Seena/Jeena ho to Aisa Jeena”. During the classes I have been taking, over the last 10 years or so, for civil service aspirants I have also emphasised the importance of my three fold mantra, namely, physical fitness, mental alertness, and emotional stability. TSR Subramanian, a former Cabinet Secretary, Government of India and 77 others, including such prominent persons like T S Krishnamurthy, N Gopalaswami, both former Chief Election Commissioners, Abid Hussain, a former Indian Ambassador to the United States, Ved Prakash Marwah a former Governor of Manipur, Joginder Singh, a former Director, Central Bureau of Investigation, filed a public interest litigation petition before the Supreme Court in the year lI have often wondered why responses in Parliament and State Legislatures elicit replies and not answers. As cleverly explained in the hilarious ‘Yes Minister’ book, the idea is not to divulge, or reveal, information in excess of what is sought. Or being ‘economical with the truth’, in the words of Sir Robert Armstrong, Cabinet Secretary of UK. An answer has to delve into the depths of the question, while a reply is content with a pro forma response.

A CHOSEN PATH

While I, no doubt, sat the civil services examinations reluctantly, and upon my father’s insistence, I feel certain, on retrospection, that I will choose no other profession in my next birth, if there is one! Quite contrary to what the legendary Groucho Marx felt on one occasion. There was this exclusive Hollywood club for the membership in which he had applied. Upon receiving intimation that he had, in fact, been admitted, he is reported to have replied, saying that he had no desire to join any club that would have a person such as he, as a member!

A sense of humour always serves to lighten the rather serious and stern ambience typical of the corridors of power. This was best brought out by a sharp exchange between B.P.R. Vithal, civil servant, economist and highly respected author par excellence, from the IAS cadre of the state of Andhra Pradesh. When the Chief Secretary asked for his reaction to a suggestion that a certain officer be posted in Vithal’s department, (Finance and Planning), Vithal’s characteristic reply was that while his department, no doubt, was known to harbour idiocy, it was cultivated and not congenital!