Undoubtedly the inventions of science have given new dimensions to human life, but if these wonders and inventions become disastrous, then what will we do?

By Abhijit Chanda

- Two deadly inventions: leaded gasoline & chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were created by American chemist Thomas Midgley Jr

- The growing amount of lead in the atmosphere led to plummeting IQ points in kids worldwide

- In the 16th century, Spanish papeletes were used to roll the remains of cigar butts by beggars in Seville, which were the first cigarettes

- Tobacco kills more than 8 million people each year, including 1.2 million second-hand smokers

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”~ George Santayana, Philosopher.

HUMAN ingenuity is almost limitless and has transformed intrepid hunter-gatherers into a burgeoning species that has moulded its planet’s resources to fulfil its needs. Every step along the way, we have solved the problems we have faced with innovations and discoveries that have shaped our path.

However, even the most harmless of such endeavours can have devastating consequences, as we will discover in this article. Many incredible inventions have changed the world for the better, but some have taken dark turns. Does that mean science is not to be trusted? That our meddling with mother nature is backfiring, and she wants revenge?

Of course not! Science is simply a way to understand our world and universe and also a method to develop tools that can help us. But almost any tool can be turned into a weapon in the wrong hands. Our beloved cars can kill and pollute our air, and our oh-so-dear mobile phones are damaging our planet through the mining of rare earth minerals. Today, I present to you some of our biggest mistakes. We must learn from their consequences and remain cautious in our explorations of nature.

Products, like fridges, air conditioners, and even aerosol cans, started using Freon; holes in the ozone layer in the stratosphere began showing up, mainly over the South Pole

LEADED FUEL

Let’s start with one of the most infamous innovators ever. He has altered the Earth’s atmosphere more significantly than any other single organism in Earth’s history, as was claimed by historian John McNeal. His inventions have killed millions, and we are still dealing with their aftereffects.

Before the 1920s, cars had to be cranked to start because the gasoline of the early 20th century was of poor quality and caused engine knocking, which reduced both power and fuel efficiency and led to breakdowns. This was a tedious practice, leading to injuries. The Cadillac Model 30 was the world’s first crank-less car. But it had a lot of engine knocking, caused by low octane petrol combusting on compression instead of the spark plug. So in 1916, in the US, Charles Kettering, the inventor of the electric starter, asked one of his employees, Thomas Midgely Jr to find a petrol additive that would make car engines run more smoothly.

A bespectacled chemical engineer from Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, Midgely Jr started working on testing hundreds of different substances to find an inexpensive additive to solve the knocking problem. In 1921, after working on the issue for 4 years, Midgley discovered tetraethyl lead (TEL) as the perfect additive. Midgely may have known the consequences but pushed on, knowing it would make the company a healthy profit. Midgley and Kettering were by then working for General Motors (GM) tied up with Standard Oil (now Exxon) and Du Pont to form the Ethyl Corporation to mass-produce the new oil.

The chemical factory built to fill the demand for the new oil soon had workers dying of lead poisoning. Midgely appeased the outcry by inhaling TEL and putting it on his hand during a press conference.

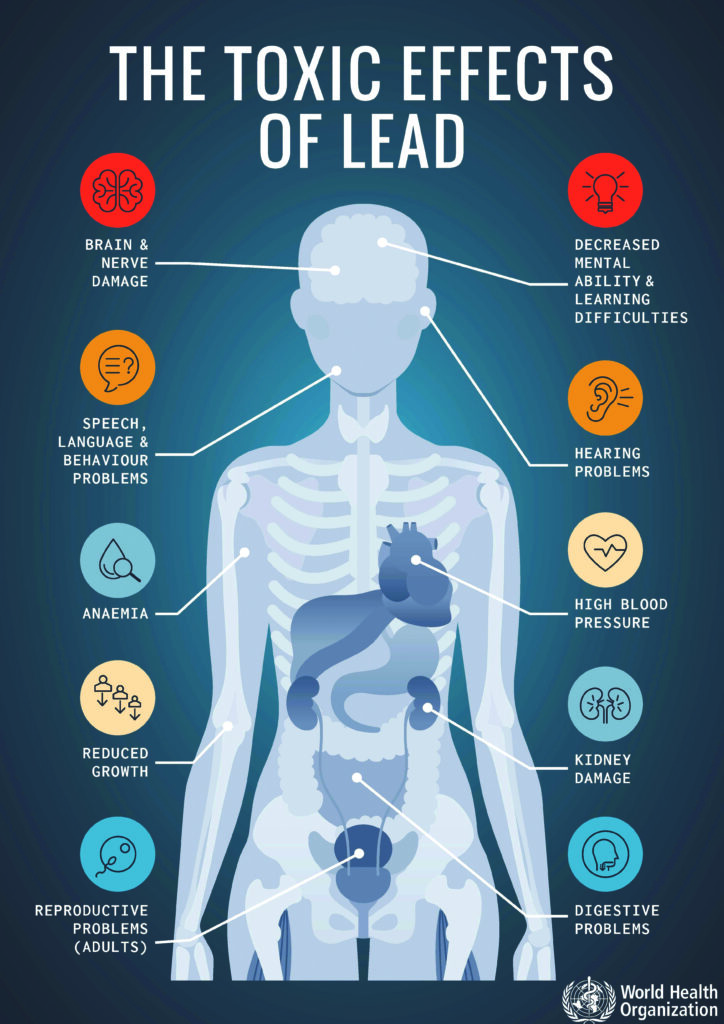

Lead gets stored in bones and poisons people for many years after contact. It wears away the myelin sheaths around the axons in the brain, preventing the release of neurotransmitters leading to tingling in the hands and feet, headaches and memory loss

The effects of lead poisoning were well known then, even to Midgley Jr. Lead gets stored in bones and poisons people for many years after contact. It wears away the myelin sheaths around the axons in the brain, preventing the release of neurotransmitters leading to tingling in the hands and feet, headaches and memory loss. Children are particularly susceptible, in whom it can lead to learning disabilities and developmental problems.

The growing amount of lead in the atmosphere led to plummeting IQ points in kids worldwide. According to one paper, researchers estimate the accumulated loss of over 800 million IQ points across the US.

A study by LH Needleman et al. in 1996 shows a direct correlation between the rise and fall of lead exposure in children due to leaded petrol and violent crime trends per 100,000 seen across many countries worldwide 20 years later. The study also found that those arrested for violent crimes were four times more likely to have high concentrations of lead in their bones. Lead exposure in children also leads to more delinquent behaviour and violent crimes as they grow up. Lead also hardens arteries and leads to heart trouble. Some estimates blame lead for being the cause of over 100 million deaths globally due to heart failure.

Leaded petrol wasn’t phased out in the US until 1984. The WHO officially banned it in 2004. Most countries have phased out leaded fuel, but its effects are still felt worldwide.

TOXIC CHLOROFLUOROCARBON

Thomas Midgley’s next project was finding an alternative to refrigerants used in fridges in the 1920s.Through his invention Midgley wanted to solve the problem with General Motors refrigerators, which were becoming a popular household appliance in the US. Midgley led the scientific team that in 1928 developed a non-toxic and non-flammable refrigerant called dichlorodifluoromethane, the very first of the chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which was sold under the brand name Freon-12.

He discovered a chlorofluorocarbon (CFC), Freon, in the late 1920s. Freon turned out to be safer than the common refrigerants of the time, which were either toxic or flammable. In another stunt to demonstrate its safety, Midgley inhaled a lungful of the gas and blew out a candle during a press conference to demonstrate its safety. This time, Midgely was right to assume it wasn’t harmful to humans, at least not directly.

Freon is a stable molecule lighter than air, so when it’s released into the atmosphere, it rises high into the stratosphere. Midgely didn’t know that if a molecule of Freon were hit by ultraviolet light while it was in the stratosphere, a chlorine atom would break off the molecule and react with an ozone molecule creating chlorine monoxide and oxygen gas.

As more and more products, like fridges, air conditioners, and even aerosol cans, started using Freon, holes in the ozone layer in the stratosphere began showing up, mainly over the South Pole. This caused a sharp rise in cataracts and skin cancer cases as the hole shifted to cover other landmasses in the southern hemisphere.

CFCs are also greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide, but over 10,000 times more potent and have already contributed to global climate change.

Thankfully, the Montreal Protocol was put in place, banning the use of Freon and other CFCs. Various replacements for CFCs have already been found before further damage is incurred to the environment, and the hole in the ozone layer is slowly healing. However, it will take many more years before it’s completely recovered.

DEADLY AGENT ORANGE

The invention that lives in infamy and somehow sounds like a character out of a James Bond story – Agent Orange – is a herbicide and defoliant chemical developed by the United States Army in the 1940s.

Arthur W Galston, a plant biologist In 1943 tried to find a chemical that could accelerate the growth of soybeans and even let them grow over a short season. At the University of Illinois, he had experimented with a plant growth regulator, triiodobenzoic acid, and found that it could induce soybeans to flower and grow more rapidly. However, in higher concentrations, he noticed that the chemical made all the leaves fall off the soybean crops and destroyed them.

His work developed a substance which later came to be known as Agent Orange – a 50-50 mixture of two herbicides: 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T). He discovered the manufacturing process also created a byproduct of a particular chemical called 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TPDD) – a member of the highly toxic dioxin family of chemicals. However, the lethal effects of dioxin were not known at the time.

The US Army didn’t wait for that information. Working with the University of Chicago, they discovered that this compound could destroy the crops of enemies. They manufactured it en masse and shipped it to Vietnam in orange-striped barrels, giving it the name Agent Orange. Other herbicidal concoctions that accompanied it were Agents Blue, Purple and White. The names derived from colour-coded bands painted around storage drums holding the herbicides.

The US initiated Operation Ranch Hand in 1961 and sprayed about 86 million litres of herbicides over 4.5 million acres of land – forest and farms in Vietnam – to deprive the Vietnamese soldiers of cover and sustenance. This caused more than 400,000 fatalities and disabilities among Vietnamese and Americans and half a million birth defects.

The use of the herbicide in the neutral nation of Laos by the US Forces secretly, illegally and in large amounts remains one of the last untold stories of the American war in Southeast Asia. At a conservative estimate, at least 600,000 gallons of herbicides rained down on the ostensibly neutral nation during the war. The use of herbicide Agent Orange in Vietnam and Laos in the 1960s has its devastating effects on river ecosystems of these two countries.

Among the Vietnamese, exposure to Agent Orange is considered to be the cause of an abnormally high incidence of miscarriages, skin diseases, cancers, birth defects, and congenital malformations dating from the 1970s.

Galston continued to study Agent Orange and dioxins and their effects on lab rats. He discovered the rats quickly developed cancer and died. He even went to Vietnam to study its impact there.

He said, “I thought it was a misuse of science. Science is meant to improve the lot of mankind, not diminish it – and its use as a military weapon I thought was ill-advised.” He brought together a lobby of fellow scientists and convinced President Richard Nixon to stop spraying Agent Orange in 1971.

Dioxin is still in the soil in Vietnam, and its effects are felt to this day.

The top-secret Manhattan Project, with some of the world’s most brilliant scientists – including Enrico Fermi, Richard Feynman, Ernest Lawrence, and Harold Urey – led by Robert Oppenheimer, was initiated to help the US develop its own nuclear weapons

DAMNABLE INVENTION – DYNAMITE

In 1847, an Italian chemist, Ascanio Sobrero, developed an oily substance that tasted sweet and gave him a headache that lasted hours. It was nitroglycerine, later used to treat high blood pressure and, more infamously, as an explosive.

Nitroglycerine was a volatile substance that could spontaneously explode if disturbed too much.

The Swedish industrialist, engineer, and inventor Alfred Nobel used to build bridges and buildings in his nation’s capital Stockholm. It was his construction work that inspired Nobel to research new methods of blasting rock. So in 1860, Nobel first started experimenting with an explosive chemical substance called nitroglycerin. He was studying this incredible substance and discovered that, if it was mixed in with a particular type of clay (silica) that would turn the liquid into a malleable paste, he could make it completely safe to hold and transport, yet still be able to make it explode with a detonator, or blasting cap, that provides the right amount of energy for the reaction to start. Dynamite was born.

Nobel then developed ways to mass produce and transport dynamite, which was used in everything from demolition to mining to warfare. It became the basis of many forms of explosives and missiles that went on to take millions of lives over the rest of history.

This unfortunate use of dynamite followed Nobel for the rest of his life, who wanted to change his legacy to be more..well..Noble. So he created a fund to reward people who made the most significant steps towards benefiting all of humankind. And the Nobel Prize was born.

On the other hand, medical doctors had noticed that those working in nitroglycerine and dynamite factories had reduced chest pain and rarely had high blood pressure. Further study into these effects led to nitroglycerine being developed into a perfectly safe and effective treatment for high blood pressure.

HARMFUL DDT

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, or DDT, was one of the most commonplace pesticides. DDT has humble origins for a chemical that would eventually reach much of the world. First discovered in 1873 by an Austrian chemist Othmar Zeidler, the compound did not receive serious attention until a 37-year-old Swiss chemist named Paul Herman Muller synthesised it again in 1936.

Muller developed the chemical while trying to identify the particular toxic ingredient in two other insecticides that he had recently invented, Gesarol and Neocid. His investigation eventually yielded dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, which he named DDT. Promptly patented in 1940 by Muller’s employer, a dye-manufacturing company named Geigy, the chemical immediately proved to be incredibly powerful. Over the next several decades, DDT would become one of the most significant and controversial chemicals of the twentieth century.

Muller even won a Nobel Prize for its invention! I don’t know how Alfred Nobel would feel about that now.

In the late 1930s, the US military used DDT to protect soldiers against insect-borne diseases. They needed an effective insecticide that they could safely apply to clothes and blankets. DDT was a miracle solution as it could kill almost any pest it came in contact with. DDT worked immediately and at low dosages. In the 1940s and 50s, it was widely used in the United States in the agricultural and pest control industries.

Then, evidence emerged that DDT wasn’t as safe as many thought. It was in the food, meat and dairy products and was absorbed by touching products contaminated with DDT. It could cause cancer along with heart and lung diseases.

Some of the DDT absorbed is converted into the metabolite dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) and stored in the body’s fat tissues. In pregnant women, these toxins were passed to the foetus and could also be found in breast milk, which exposed nursing infants to this deadly chemical.

In 1962, a book called Silent Spring by Rachel Carson spoke of how DDT and other pesticides had been shown to cause cancer and fertility issues. DDT, the most powerful pesticide the world had ever known, exposed nature’s vulnerability. Unlike most pesticides, whose effectiveness is limited to destroying one or two types of insects, DDT was capable of killing hundreds of different kinds at once. It also described how their agricultural use threatened wildlife, particularly birds.

Silent Spring took Carson four years to complete. It meticulously described how DDT entered the food chain and accumulated in the fatty tissues of animals, including human beings, and caused cancer and genetic damage.

This book led to a public outcry, following which, in 1972, a ban was placed on DDT’s agricultural use in the United States.

This deadly pesticide has had a worldwide ban since 2004. However, it is still used in certain third-world countries to fight against Malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases.

SMOKE OF CIGARETTE

This isn’t as much a modern-day invention as an ancient tradition. Even the ancient Aztecs seemed to have smoked tobacco stuffed into a hollow reed or cane tube. Crushed tobacco rolled in corn husks and other vegetable skins were smoked by the natives of Mexico, Central America, and parts of South America.

Tobacco kills more than 8 million people each year, including 1.2 million second-hand smokers, cigarettes are still a perfectly legal addiction for people worldwide

When the conquistadors invaded these lands, they brought back something closer to a cigar to Spain.

Then, in the early 16th century, Spanish papeletes were used to roll the remains of cigar butts by beggars in Seville, which were the first cigarettes. These cigarillos (Spanish: “little cigars”) spread to Italy and Portugal, where Portuguese traders carried them and Russia.

When the French encountered them in the Napoleonic Wars, they named them cigarettes. Later, in the Crimean War, the British and French discovered Turkish cigarettes around the same time that the US took on the habit.

Washington Duke, an American farmer, first made commercially available cigarettes in 1865 on his 300-acre farm in Raleigh, North Carolina, USA. His hand-rolled cigarettes were sold to soldiers at the end of the Civil War.

In 1880, James A Bonsack invented the cigarette-making machine that wholly automated and industrialised the process, making cigarettes much more accessible and started a widespread trend of cigarette smoking. Bonsack’s machine could make 1,20,000 cigarettes a day. He went into business with Washington Duke’s son James ‘Buck’ Duke and built a factory in 1881. They produced 10 million cigarettes in the first year and by 1883, the workers were rolling 250,000 cigarettes daily and about 1 billion cigarettes five year later. The device was then imported to England in 1883.Through the late 1940s and 50s, cigarettes were considered quite a harmless addiction.

Richard Doll, a researcher in Britain, working for the Medical Research Council, and Bradford Hill, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene, began looking at lung cancer patients in London hospitals. Out of the 649 cases of lung cancer, only two of the patients were non-smokers.

As the years went on, the link between tobacco and lung cancer and many other diseases became more robust. By 1956, the industry was being reprimanded with higher taxes, restrictions on advertising, and prohibition of sales to children across the US.

Today, those restrictions have grown to good effect in many countries. But, although tobacco kills more than 8 million people each year, including 1.2 million second-hand smokers, cigarettes are still a perfectly legal addiction for people worldwide.

CATASTROPHE NUCLEAR BOMB

Leo Szilard was waiting to cross the road near Russell Square in London when the idea came to him, a eureka moment in inventing nuclear bomb, it was 12 September 1933. A little under 12 years later, the US dropped an atom bomb on Hiroshima. The path from Szilard’s idea to its deadly realisation is one of the most remarkable chapters in the history of science and technology. The deadliest weapons ever made are nuclear warheads. Their death toll isn’t high, but they can potentially destroy the world. That’s the potential displayed at Hiroshima and Nagasaki as nuclear fission bombs were dropped on them. Not only did this lead to the Cold War but also the eventual push towards nuclear disarmament.

The process of nuclear fission, a chain reaction where neutrons can split atoms with a massive release of energy, was first discovered by Italian scientist Enrico Fermi in 1934. In 1938, two German scientists, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman, conducted experiments where neutrons from radium and beryllium were shot into uranium, resulting in a lighter element, barium, left over.

Much research was initiated to find suitable applications for this immense amount of energy being discharged. While some scientists were looking for peaceful ways to harness this power to generate electricity, others started working on more sinister applications.

The Germans were the first to look at uranium-based weapons that could be made using this process as World War II raged on. In August 1939, Albert Einstein wrote to the US President Franklin Roosevelt to warn him that the Nazis were working on a new and powerful weapon: an atomic bomb. Fellow physicist Leo Szilard urged Einstein to send the letter and helped him draft it to alert Roosevelt to this situation.

But in July 1940, the US Army Intelligence office denied Einstein the security clearance needed to work on the Manhattan Project because the left-leaning political activist was deemed a potential security risk.

The top-secret Manhattan Project, with some of the world’s most brilliant scientists – including Enrico Fermi, Richard Feynman, Ernest Lawrence, and Harold Urey – led by Robert Oppenheimer, was initiated to help the US develop its own nuclear weapons.

In the meantime, in 1940, Glenn Seaborg, at the University of California, Berkeley, created plutonium by irradiating uranium. Around the same time, Fermi found a way to create a sustainable nuclear fission reaction.

On 16th July 1945, the first successful nuclear test was conducted in Alamogordo, New Mexico, USA. Then, the dreaded moment came on 6th August 1945, at 8:16 am Japanese time. The Enola Gay, an American B-29 bomber, dropped the world’s first atom bomb, named Little Boy, over the city of Hiroshima. Around 80,000 people were killed immediately, and another 35,000 were injured. Three days later, Fat Man was dropped on Nagasaki. Another 40,000 people were killed instantly. In total, nearly 225,000 lives were lost that day, with many more following due to the nuclear fallout.

THE LESSONS LEARNED

This isn’t an exhaustive list by any means. Our history holds many more painful stories of science gone awry in the wrong hands. But I hope they remind us that we are a young species. At best, we are coming out of our adolescence, testing our limits and pushing ourselves to see how invincible or vulnerable we are. The lessons these inventions have shown us is that our love of exploration and discovery is equal to our tendencies toward greed and power.

I wish I could take refuge in the thought that the worst may be behind us. But when we see, even today, the power-hungry despots determined to continue fighting for land, resources and beliefs, we must remember that we are not out of the woods yet. We have learned some lessons as a species, but we have a long way to go before we are at peace with ourselves.