That farsightedness and grit made Jawaharlal Nehru and the new government he led were aimed at achieving ‘an economic take-off or an early industrial and agricultural breakthrough’ – essentials for constructing an ‘effective democracy’ to be caressed by the working people

By Sankar Ray

- The path of development of India, once it would become free, was first scripted at the Karachi Congress in 1931

- The man behind the National Planning Committee- was the world-famous astrophysicist, Dr Meghnad Saha

- Subhas Chandra Bose in his presidential address envisaged the setting up of ‘national planning commission’

- federal structure, State List and Concurrent List, five-year plans, etc., were conceived by the freedom movement

THE founders of the Indian Republic had a foresight during the freedom struggle on how to manage Independent India that India’s first Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru encapsulated in three words together –‘tryst with destiny’ at the moment India woke into freedom. Nehru spent nearly ten years in freedom – the longest among the freedom fighters excluding Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. That farsightedness and grit made Jawaharlal Nehru and the new government he led were aimed at achieving ‘an economic take-off or an early industrial and agricultural breakthrough’ – essentials for constructing an ‘effective democracy’ to be caressed by the working people.

The Indian National Congress (INC), which represented the ‘national bourgeoisie’, the Naxalites’ characterization of them as ‘comprador bourgeoisie’ was parroting of what the Communist Party of China – actually Mao Zedong – formulated without going in-depth; had the Government of India been ruled by the comprador bourgeoisie, it hadn’t liberated Goa from the Portuguese colonialism nor helped the Liberation struggle of Bangladesh achieve success, first scripted the path of development of India once it would become free at the Karachi Congress of INC in 1931.

KARACHI RESOLUTION

It ‘started to envisage firmer control of the Indian economy. In its programme for an Indian government’, it declared, “The State shall own or control key industries and services, mineral resources, railways, waterways, shipping and other means of public transport”, wrote David Lockwood in his The Indian Bourgeoisie: – A Political History of the Indian Capitalist Class in the Early Twentieth Century. The resolution adopted, stated, “This Congress is of the opinion that in order to end the exploitation of the masses, political freedom must include real economic freedom of the starving millions. In order, therefore, that the masses may appreciate what Swaraj, as conceived by the Congress, will mean to them, it is desirable to state the position of the Congress in a manner easily understood by them.

The Congress, therefore, declares that “any constitution that may be agreed to on its behalf, should include the following items, or should give the ability to the ‘Swaraj Government’ to provide for them”. The Rashtrapati (before Independence, the Presidents of the Indian National Congress were called Rashtrapati) at the Congress was Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. The Congress outlined the future constitution of Independent India.

Nehru wrote later that the Karachi resolution took a step, a very short step in a socialist direction by advocating the nationalisation of key industries and services, and various other measures to lessen the burden on the poor and increase it on the rich. Mahatma Gandhi himself endorsed state intervention to the extent that it was needed to protect Indian industries: “I am an out-and-out protectionist’, he declared, endorsing protection for the cotton industry and the reservation of coastal shipping for Indians” (Lockwood).

IDEA OF PLANNING COMMISSION

Congress Leader Subhas Chandra Bose in his presidential address at the 51st session at Haripura in February 1938, envisaged that the first task of the Government of Free India would be to set up a ‘National Planning Commission’. He said: “I have no doubt in my mind that our chief national problems relating to the eradication of poverty, illiteracy and disease, and to scientific production and distribution can be effectively tackled only along socialist lines. The very first thing which our future national government will have to do would be to set up a commission for drawing up a comprehensive plan for reconstruction. This plan will have two parts—an immediate programme and a long period programme. In drawing up the first part, the immediate objectives which will have to be kept in view will be threefold: firstly, to prepare the country for self-sacrifice; secondly, to unify India; and thirdly, to give scope for local and cultural autonomy.” Bose foresaw India’s freedom and in order to accelerate the task of national reconstruction and fight against poverty. He appointed Nehru as the first Chairman of this Committee.

“The very essence of this planning”, Nehru wrote, “was a large measure of regulation and coordination. Thus while free enterprise was not ruled out as such, its scope was severely restricted. Defence industries were to be state-owned, while ‘key industries’ would be state-controlled. Such control of these industries, however, had to be rigid.”

The 15 August 1947 was ‘the first stop, the first break—the end of colonial political control: centuries of backwardness were now to be overcome, the promises of the freedom struggle to be fulfilled, and people’s hopes to be met’

The Congress manifesto for the elections of December 1945 advocated ‘social control of the mineral resources, means of transport and the principal methods of production and distribution in land, industry and in other departments of national activity, as well as ‘large state farms.

The man behind the idea of national planning -the National Planning Committee- was the world-famous astrophysicist, Dr Meghnad Saha who went to jail during boyhood when he plunged into the freedom struggle. Saha was introduced to Subhash Chandra Bose by Rabindranath Tagore when the idea of national planning was in Saha’s thoughts. He was inspired by the five-year plans in the Soviet Union, Bose was then the Congress Rashtrapati. Bose was impressed. The idea of putting Sir Mokshagundam Vishveshwarayya, a legendary civil engineer, at the helm came up. But Saha suggested that the national planning panel be headed by an influential political leader. So the name of Jawaharlal Nehru came up.

THE REST IS HISTORY

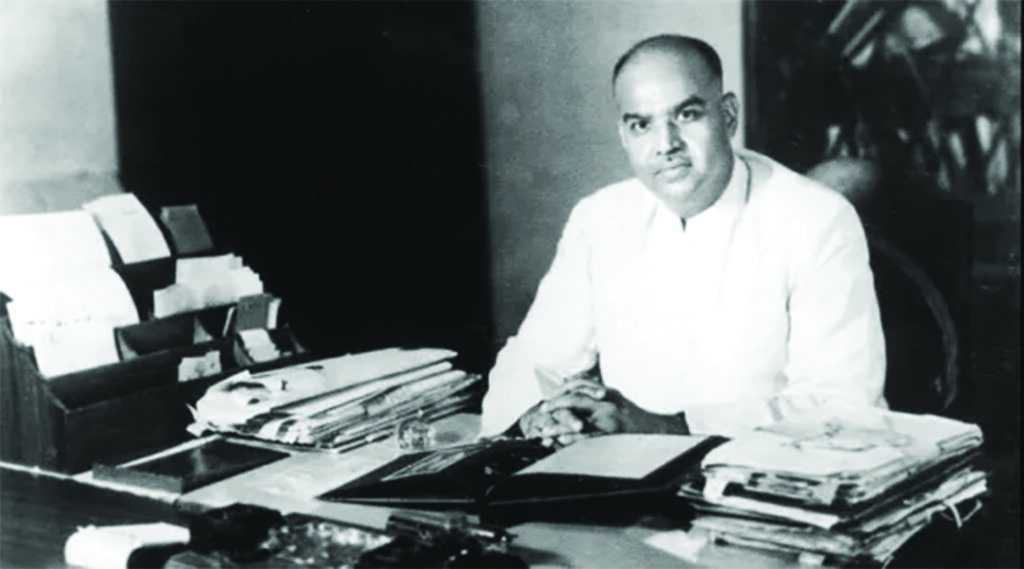

Interestingly, it was Syama Prasad Mookerjee, who was independent India’s first Minister of Industry and Commerce, who tabled the Industrial Policy Resolution of 1948 that included the formation of the National Planning Commission, stating, “Careful planning and integrated effort over the whole field of national activity are necessary: and the Government of India proposes to establish a National Planning Commission to formulate programs of development and to secure their execution.” A few years thereafter Mookerjee quit the ministry, headed by India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and formed the Bharatiya Jana Sangh.

The Planning Commission was set up in March 1950. The first Five Year Plan focused on agriculture more than industry, which was focused more on the second Five Year Plan. The thrust was on a mixed economy. However, the Planning Commission was abolished in 2014 by Narendra Modi after taking over as India’s premier. In its place, NITI Aayog (National Institution for Transforming India) was set up – formed via a resolution of the Union Cabinet in January 2015.

NITI Aayog is the premier policy ‘Think Tank’ of the Government of India, for providing both directional and policy inputs alongside designing strategic and long-term policies and programmes for the Government of India. It is supposed to foster cooperative federalism through structured support initiatives and mechanisms with the states on a continuous basis, recognizing that strong states make a strong nation. As such, it is a state-of-the-art resource centre, with the necessary resources, knowledge and skills. But unlike the Planning Commission, NITI Aayog does not enjoy autonomy.

Interestingly, it was Syama Prasad Mookerjee, who was independent India’s first Minister of Industry and Commerce, who tabled the Industrial Policy Resolution of 1948 that included the formation of the National Planning Commission

MODEL OF DEVELOPMENT

From the wee hours of day one in Independent India, the new government ‘was committed to a democratic and civil libertarian political order and a representative system of government based on free and fair elections to be conducted on the basis of the universal adult franchise’, succinctly wrote Bipan Chandra, Mridula and Aditya Mukherjee in their book, “India Since Independence” 15 years ago.

Adult franchise, federal structure based on trichotomy of Central List, State List and Concurrent List in the Constitution of India, five-year plans, public sector at the helm etc were conceived by the freedom movement. The tone was set by none other than Mahatma Gandhi who wrote in Young India in 1925, the year of the founding of RSS, “Real Swaraj will come not by the acquisition of authority by a few but by the acquisition of the capacity by all to resist authority when it is abused. In other words, Swaraj is to be obtained by empowering the masses to a sense of their capacity to regulate and control authority.”

There was the ‘Nehruvian consensus’ comprising Nehruvian ideals and vision over the alternative discourses regarding the preferred principles of political, social and economic restructuring of postcolonial India

India’s independence, intimately involving people, (take, for instance, the spontaneous participation in the historic Quit India movement, by tens of thousands, braving colonial guns.) It was the beginning of a new era with the goal of overcoming the colonial legacy of economic under-development, gross poverty, near total illiteracy, the wide prevalence of disease and stark social inequality and injustice. It was too destructive a model of ‘development of under-development ( A Gunder Frank) which continued mostly in Latin America and Africa even after their independence).

The 15 August 1947 was ‘the first stop, the first break—the end of colonial political control: centuries of backwardness were now to be overcome, the promises of the freedom struggle to be fulfilled, and people’s hopes to be met’.

After the achievement of freedom, the first independent national government took up an innovative policy of what eminent political theoretician Prof Sudipta Kaviraj defined as ‘creative capitalism’, thanks to India’s thinker Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. It was a mixed economy where the public sector had to play a vital role. This was very unlike the capitalist path, dominated by multinational corporations which were vectors of neo-colonialism or ‘invisible imperialism’.

India’s top leaders in the private sector gained from the mixed economy which simultaneously created jobs for millions for whom the Nehru government ensured job security in keeping with the commitment during the freedom movement since the late 1930s. When the second Industrial Policy Resolution was announced in 1956, putting the public sector in ‘commanding heights’, there was a panic among a section of industrialists. But one of the doyens among Indian industrialists, Ghanshyam Das Birla wrote to then President of World Bank Eugene Black that the new Industrial Policy Resolution was the ‘largest single fillip’ to the private sector. He was right as the leading public sector undertakings like the then Hindustan Steel Limited (subsequently rechristened as the Steel Authority of India Limited) would manufacture products that were to be input for the private sector at cheap prices.

There was the ‘Nehruvian consensus’ comprising Nehruvian ideals and vision over the alternative discourses regarding the preferred principles of political, social and economic restructuring of postcolonial India. This dominance was a product of Nehru’s personality cult and associated statism, that is, the overarching faith in the state and the leadership. The public sector created the ‘steel frame’ of the ‘enlightened technocratic bureaucracy’ that osmotic ally became, by default, a vehicle for the ‘activist state’.

Nehru envisioned a new Indian polity for which rapid industrialisation would help the battle against mass poverty achieve success in striking contrast with the Gandhian economic vision centred on household production. But the vision fell through at least in the eradication of poverty. The rich-poor hiatus widened further

An economic modernist, Nehru envisioned a new Indian polity for which rapid industrialisation would help the battle against mass poverty achieve success in striking contrast with the Gandhian economic vision centred on household production. But the vision fell through at least in the eradication of poverty. The rich-poor hiatus widened further. Nehru realised this and even told the famous British scientist J D Bernal at a chance meeting in Peiping (now Beijing) in 1955, ‘ Most of my ministers are corrupt and scoundrel’. None other than him could feel bitterly that he became a hostage to the development economics consensus of his times, both in terms of its insights as well as its policy flaws. All this made him alone, his popularity among the masses notwithstanding. Nonetheless, there was overwhelming evidence not only of resurgent growth but also of a lasting transformation of a stagnant colonial enclave into an economy capable of sustained growth. But the Nehru era has gradually moved away from the uncomfortable reality, dominated by a handful of crony capitalists.