Modi’s India is no news

An Indian veteran for decades, Andrew Whitehead underscores that while India news sells, it is about society and its changes rather than about over-sold political gimmicks

THERE’S something eternal about the Indian news agenda. If you are looking at the big political themes, they have barely changed in a decade or more: the state of what the political scientist Ashutosh Varshney called ‘India’s improbable democracy’, and whether it can buck the global trend of the rise of the populist autocrat; whether the BJP will become a full-on communal party or one with a lightly worn religious identity; and how Congress – a party so wedded (padlocked might be a better word) to a political dynasty – can convincingly be seen as modern and social democratic.

India’s impressive rates of economic growth – certainly as seen from any western country – have promoted social development but not equality.

The big cities are marching upwards as well as outwards, with impressive high-rise developments to cater to an increasingly aspirational middle-class. Village India is changing too, but not as emphatically.

Foreign correspondents, of course, are almost all Delhi-based so they have a personal as well as professional interest in looking, largely forlornly, for any sign of the political will to deal with the issues besetting the capital: the pall of smog which is choking the life out of Delhi and the epidemic of sexual violence which is giving the city, in the minds of many Indians as well as outsiders, the tag of “best avoided”.

POLITICAL PARADIGMS

On a more positive note, the eruption of #MeToo in India is an emphatic statement that voices from outside the corridors of power can summon the moral authority to remould aspects of public life.

If there is a topic to be pursued with more vigour, it is how the young in what is after all a young people’s country are remaking Indian society, and may yet find a way to reshape its politics too.

The trouble is that all these themes sound more like seminar topics than news stories. It’s the job of the foreign correspondent, of course, to find the news peg and deliver the story that throws light on a commanding social or political trend.

But compared to Imran Khan’s fumbling steps in power in Pakistan, or the rise of the hard right-winger Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, or Russia’s attempts to subvert the political systems of its rivals, the range of news stories that India provides feels familiar.

“Sorry, India’s just not that ‘hot’ any more” is the refrain from news and assignment editors when foreign correspondents pitch story ideas from and about the country.

India still makes news, of course, and there’s still a team of foreign reporters – or more often these days, Indian correspondents working for global news providers – whose job is to get India noticed. But it can be an uphill task.

CORRESPONDENTS’ CONUNDRUM

I was asked recently for advice on what sort of stories about next year’s election campaign will work for global audiences.

There is no obvious answer. For those who follow Indian politics closely, it is of course an all absorbing contest which will provide news lines galore.

Anyone with a serious interest in world affairs will want to keep informed about the conduct and outcome of the world’s biggest election.

Whether it will be seen as one of the defining global news events of the year, I rather doubt. I hope I’m wrong. I’ll be doing my bit to stimulate interest in the election – but it could be a tough sell.

The just-completed mid-term elections in the United States – normally not exactly a humdinger in news terms – have attracted more global editorial interest and effort than will India 2019.

That reflects not simply the intrinsic interest of the event but also the global appetite for foreign news.

The world’s second-biggest democracy is increasingly self-absorbed – reflecting the more isolationist mindset of its administration and the intense divisions about the sort of country the US aspires to be.

India’s impressive rates of economic growth certainly as seen from any western country have promoted social development but not equality

Other nations which normally take a keen interest in India are also looking inwards. Just as next year’s election campaign gets into gear, Britain sets itself loose from the European Union, the most successful multinational organisation of our time.

Brexit will mark the biggest change in Britain’s place in the world since the unravelling of its Empire, the most spectacular act of which was the ending of the Raj in August 1947.

To those of my colleagues trying to get the sustained attention of British audiences for foreign news next year good luck with that!

UNSURPRISING MODI

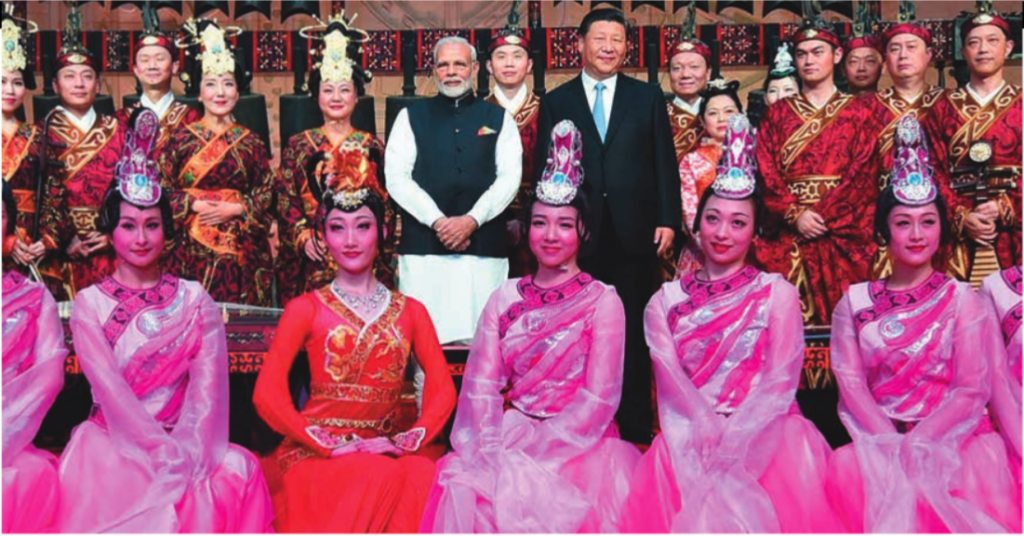

News needs an element of surprise – or at least something that’s novel. The 2014 election outcome hardly came as a bolt from the blue, but the emphatic margin of Narendra Modi’s victory was startling, and the decisive victory for a non-Congress party was historic.

The world sat up and took notice. India’s new prime minister was frostily determined not to talk to the world’s media and he cold-shouldered quite a lot of the Indian media too; but there was huge interest in the man, his political method and the ideological blend he championed.

This time round, the outcome is likely to be less sensational. There’s plenty of time yet for an electoral upset, but we are likely to be talking more about the margin of victory than about who won.

And the world feels it knows as much as it wants to about Mr Modi that’s not to say they understand the man, or the nature of the party he leads, just that he’s no longer turning heads as the new guy on the block.

As a new prime minister, Narendra Modi travelled the world, enthused the Indian diaspora and struck-up at first glance unlikely friendships, notably with Barack Obama.

CHINA WINNING

Of late, he’s been more focussed on his domestic profile – as makes sense, given the electoral cycle. His most eye-catching domestic initiative – that bonfire of the bank notes which is hidden behind the mealy-mouthed word ‘demonetisation’ – was so outlandish that much of the world looked on in mute incomprehension.

The specialist financial outlets aside, a lot of the coverage was knockabout stuff – so how come a guy with a thick wad of bank notes can’t buy lunch? – rather than giving the subject the scrutiny that it was due.

India’s new prime minister was frostily determined not to talk to the world’s media and he cold-shouldered quite a lot of the Indian media too

The less combative tone between India and its neighbour to the west hardly a thaw, but at least a pause in the deepening spiral also takes something of the urgency away from coverage of India and its foreign policy.

On the other flank, China is now indubitably the pre-eminent Asian power with the most robust economy, strongest military and most interventionist outlook.

If there’s a battle for Asian supremacy, then China has won – and that’s reflected in the news agenda too. For many news organisations, a strong bureau in Beijing is essential while Delhi is ‘nice to have’.

There’s finite space for foreign news, and limited budgets too. So as new themes and nations edge up the global news agenda, it inevitably means that others fall away.

NEWS BUSINESS

Breaking news will always be covered – that grim tangle of tales about death and destruction, whether natural disasters or caused by human agency.

The competition for story commissions on the underlying stories – the ones that don’t demand the top headline but often tell you much more about how the world is changing – is intense, and it’s all about engaging with the online audience.

There is a technology-driven aspect to the changing appetite for foreign correspondents’ stories. Once newspapers and magazines were stuffed full of articles which, in all probability, had a tiny readership, at least beyond the first few lines.

The big cities are marching upwards as well as outwards. Village India is changing too, but not as emphatically

Now that so much news is consumed digitally – and on phones above all – editors for the first time know precisely how many people see each story, how long they spend on it and whether they get anywhere near the end before they lose interest.

Stories which don’t appeal simply don’t get commissioned. And when correspondents insist ‘there’s huge interest in this sort of story’, editors can demonstrate that no, there isn’t.

The digital revolution of course means that commissioners can never say: sorry, we don’t have space. In marked contrast to news bulletins, newspapers and magazines, there’s no limit to the number of stories that can be posted online.

But there’s another side to that – as long as you have a few fresh stories, there’s no need to solicit news content simply to fill your broadcast or magazine page.

Indeed, the digital statistics demonstrate what is simply common sense – that stories that aren’t prominent on the news front page, and that don’t have promotional displays, don’t attract eyeballs.

SO WHY DO THEM?

All this may seem a counsel of despair. It isn’t intended to be. The challenge is to find the stories which resonate with audiences and with editors – perhaps not so much about politics and political process, but about gender, lifestyle, entertainment and all the issues that attract the attention of under-25s, the generation which is so hard to reach through the old-style news platforms.

It’s about taking stories about individuals and using them to open up an exploration of social fault lines, the points of tension which illuminate the social and political landscape.

It’s about convincing the digital world to care not so much about India, the political entity, as about Indians, their achievements, ambitions and concerns. So as ever, the role of the foreign correspondent is to push, and push hard, for stories which offer a rounded account of how India is growing.

It’s always been a hugely complex country, and in making the Indian story accessible to audiences in other countries, it’s so important to avoid stereotypes and crude caricature.

INDIA NEWS

Increasingly, news outlets want the human angle that illuminates a wider theme. And India is such a riot of noise, opinion, strong visuals and articulate voices – it gives any correspondent a head start.

And what really encourages take-up of Indian news stories is that, for almost all foreign correspondents who spend time here, India is not just another posting. They build up a strong affinity with the place – that doesn’t mean that they take sides, but it does mean that they care.

Mind you, if there’s one thing harder than selling an Indian story to a global news provider, it’s interesting an Indian news outlet in a global story. I’ve got lots of experience of both.

It’s hazardous to generalise, but by-and-large Indian interest in news remains intensely parochial. Whatever the impact of globalisation, most consumers of news are resolutely uncurious about the world.