Flesh Trade have become part of what is called Kathmandu’s ‘entertainment’ industry of at least 13,000 women

By Sutirtha Sahariah

THAMEL! The glitzy, sleazy underbelly of Kathmandu.There you could meet Sunita, serving you drinks in a tiny closet in a joint. You have all the right to bodily misuse her, and she does not have the right to refuse and there would be no “Me Too”! After all, she works in a ‘cabin restaurant’, where this is the price she pays to stay alive.

She does not always get paid. The greasy, greedy men she hates. But this is what she had come to after the Maoists ditched her and she was no longer a ‘girl soldier’.

Like her, there are others working in ‘duet restaurants’, which feature live music shows, which includes palming and pawing. Or the massage parlours, where too male carnality rules the roost. Unbridled. Known to the authorities….

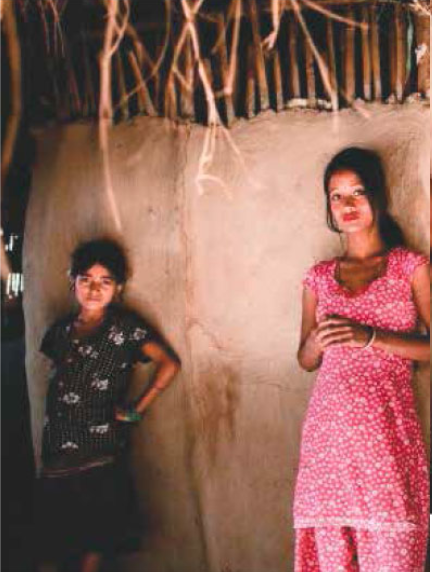

They call this Nepal’s ‘entertainment industry’, where you will also meet Dhan Kumari and many others, whom I got to interview. In 2016, as a part of wider study funded by Britain’s Department of International Development (DFID) that explored the relationship between Women, Work and Violence in Nepal, Myanmar and Pakistan, I interviewed thirty women and conducted to two focus groups of ten women each engaged in sex and informal entertainment industry in Kathmandu, Nepal.

But this is not just a story of tears. This is the story of hundreds of such women who fought it out and have become independent members of society.

INSURGENCY’S VICTIMS

Seema, 20, was six-years-old when she was abducted by Maoist rebels from her village in Sindhupalchok, 66 km north-east of Kathmandu, during the ten-year armed conflict with the government forces that ended in 2006.

Her father, who was in the Maoist army, was killed by the government forces. “They said I have to avenge my father’s death. I was forced to use the gun; I was used as a soldier. I was in the entertainment wing (advocacy) which was made up of children.

Its purpose was to influence people with the Maoist ideology. I was a dancer. I used to carry guns and ammunition. I was made to kill a lot of people. Every time they came across someone, they would say he is your father’s killer so shoot him,” says Seema.

Like Seema, Dhan Kumari alleges that she was abducted by the Maoist during the height in the insurgency in 2002, as they suspected that her brother was in the Nepal army. She says she and many other girls were raped and tortured by the Maoists forces known as the People’s Liberation Army.

Seema returned home but wasn’t accepted by society. “I was ostracised. There were families in the village that had a member in either police or the army and were killed. They blamed me for that.”

Seema was married off soon at the age of 15, but the 2015 earthquake that hit Nepal killed her husband and destroyed her house. She came to Kathmandu with her six-month-old baby to start a new life.

Unable to find a proper job, she joined a massage parlour in Thamel a popular business district in the heart of Nepal’s capital Kathmandu popular with tourists.

She says “I don’t like this job. If I could remain in the village, that would have been better. In the massage parlour, we are pushed to have sexual encounters with customers. I hate this job.”

RED MENACE

One of the significant findings that emerged from the interviews conducted with the women is that the ten-year-long Maoist conflict (1996-2006) against the government forces had devastating consequences on their early lives.

It was found that one third were directly affected by the Maoist conflict; four women confirmed that they were abducted, sexually abused, raped and used as child soldiers

From the sample of women studied it was found that one third were directly affected by the Maoist conflict; four women confirmed that they were abducted, sexually abused, raped and used as child soldiers during the conflict.

Others, who had migrated to Kathmandu when they were very young, said the conflict was the major cause for them to leave their villages as school children were regularly abducted by the Maoist forces (PLA) and coerced to join various ranks in their forces.

The recruited girls were used as combatants, scouts, spies, porters, cooks and as part of cultural troupes.

But when the peace agreement was signed between the government and the Maoist forces, women like Seema or Kumari were simply abandoned by the PLA. Many of the top commanders in the Maoist forces went on to occupy powerful positions in the police and in the army and abandoned the objectives of the movement, which was to reframe social and gender relations at the grassroots level.

Abandoned, ostracised and unskilled, many young girls migrated to Kathmandu and found their way into the sex and entertainment industry in Kathmandu to make a living.

Recently the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) considered the sixth periodic report of Nepal at its 1631 and 1632 meetings held on 23 October 2018.

It expressed concern that the draft bill to amend the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act (TRC Act) impedes legal action for claims related to sexual and gender-based violence, including war crimes and a crime against humanity.

It has been further pointed out that women and girl victims of the armed conflict have not benefited from interim relief reparations.

There are no official figures available on the number of women working in what is largely regarded as informal entertainment industry in Nepal; a 2009 study by Terre des homes (TDH) estimated it to be 11,000 to 13,000 girls and women in Kathmandu valley alone the actual figure is believed to be much higher across Nepal.

The study also found that that child marriages, domestic violence and abandonment by alcoholic husbands and fathers are other common factors that drive women to join this sector.

Activists emphasise that post the April 2015 earthquake, that killed 8,000 people, there has been a disturbing trend of thousands of young women from the devastated regions being tricked by human traffickers to join this sector with the lure of quick money and foreign jobs.

MENUKA’S MESSAGE

Raksha Nepal is one of the leading NGOs that have been working to provide support to sexually exploited girls and women working in the entertainment sector. Its founder, Menuka Thapa herself worked as a singer in a cabin restaurant as a teenager.

She says: “I saw the girls being mistreated and exploited badly. They were also forced to perform sexual activities by the customers and the owners of the restaurants. The girls wouldn’t get paid for days but could not raise their voice for the fear of losing their jobs. I was determined to fight against such atrocities.”

Horrified by what she saw, Thapa rounded up a group of women and girls who worked there and encouraged them to speak up for their rights. She says this helped them feel more confident in firmly saying “no” to advances from the customers and owners and demanding their full wages.

Hearing about her initiative, girls from different dance bars, restaurants and massage parlours in Kathmandu started contacting her. Realising that she had hit a nerve, Thapa started the NGO Raksha Nepal (“Protect Nepal”) in 2004, when she was out of the restaurant industry, with the goal of empowering women working in informal entertainment.

Over the past 15 years, she says her charity has helped 1,623 women and girls escape from sexual exploitation.

Way back in 2008, responding to the huge surge of women working in this sector, and reports of severe exploitation and trafficking, the Supreme Court of Nepal had issued a directive to the government to set up guidelines to protect women and girls in the entertainment sector from economic and sexual exploitation.

Activists say that the guidelines have never been implemented.

LARGER CONCERNS

Recently, CEDAW expressed concern that the Human Trafficking and Transportation (Control) Act punishes women in sex and entertainment sector rather than addressing wider issues of violence and abuse at workplace.

It has recommended that the government of Nepal formulate a comprehensive policy, legislative and regulatory framework that ensures monitoring and legal protection from exploitation of women who engage in sex and entertainment industry and ensure that they are not prosecuted for engaging in such activities.

“The large number of women engaged in this industry is contributing to national economy and tourism, yet, there is a lack of social acceptance and a huge stigma attached with their professions. They are very vulnerable as they don’t have any social security. There is a critical violation of their human rights”, says Anisha Lintel of Women’s Forum for Women in Nepal.

Ratna Bajracharya, former director -general at the Department of Women and Children says: “It’s a well known fact that girls and women working in the entertainment sector are being physically and sexually abused. While the massage parlours and dance bars are legal, sex work is not, so the government ignores the matter pretending that the problems don’t exist. It is better to regulate this sector and protect the basic rights of those working in it.”

To advocate for the rights of women working in this sector, Women Workers’ Protection Union was formed in 2015 with the help of DKA Austria in Kathmandu. The union now boasts of 9,000 members.

The union leader Sabina Tamang says: “Our biggest problems are frequent raids, abuse and unlawful detention by the police. We want this to stop. Our key demands are formal recognition of our work, minimum wage and better work conditions.”

OFFICIAL STAND

Sarbendra Khanal, who at the time of this interview was a senior superintendent of Police, Metropolitan Crime Division, refuted the allegations of police atrocities. He says “We take cases of gender violence, rape or sexual exploitation very seriously. We give it a top priority and don’t leave a stone unturned while investigating such cases.

We have no problems with registered massage parlours or dance bars but as a law enforcement agency, it is the duty of the police to check any illegal activities which are seen as anti-social. We need to stop people that carry 10-12 girls in vans in the middle of the night.”

Mohna Ansari, Commissioner, Nepal’s National Human Rights Commission, describes the problem as “alarming” and says to help women affected by internal conflict Nepal has set up a National Action Plan to implement UN Security Council resolutions 1325 and 1820, and further formed good institutions and policies like the Prime Minister’s National Plan for Action against Gender-Based Violence, 2010.

“The concern is that these mechanisms haven’t been able to respond adequately to the problems of women and girls in a systematic manner. There is no political will and the ongoing political instability means all the gains made in the past are lost – gender and human rights issues are never accorded priority. These issues are a challenge for the whole Nepalese society”, she says.

A year ago, Seema met a health outreach worker, who took her to the NGO Raksha Nepal. She is now taking tailoring courses funded by UNODC. “If I had even basic education my life would have been better. If there was no war, probably I would be studying at a university. I hope that one day I can start my own tailoring shop. I want to get out of my present occupation and want to provide a good life to my child,” says Seema.

INCOME EMPOWERS

The study also found that though the informal entertainment sector is highly abusive, it also represents a transformative moment for the majority of women studied.

In part, this is because they have been able to leave behind violent husbands and destructive family/community contexts. Income has enabled them to take control and build resilience to their past traumas by connecting with other women with similar backgrounds. It has given them a voice, rebuild their lives and invest in their children’s education.